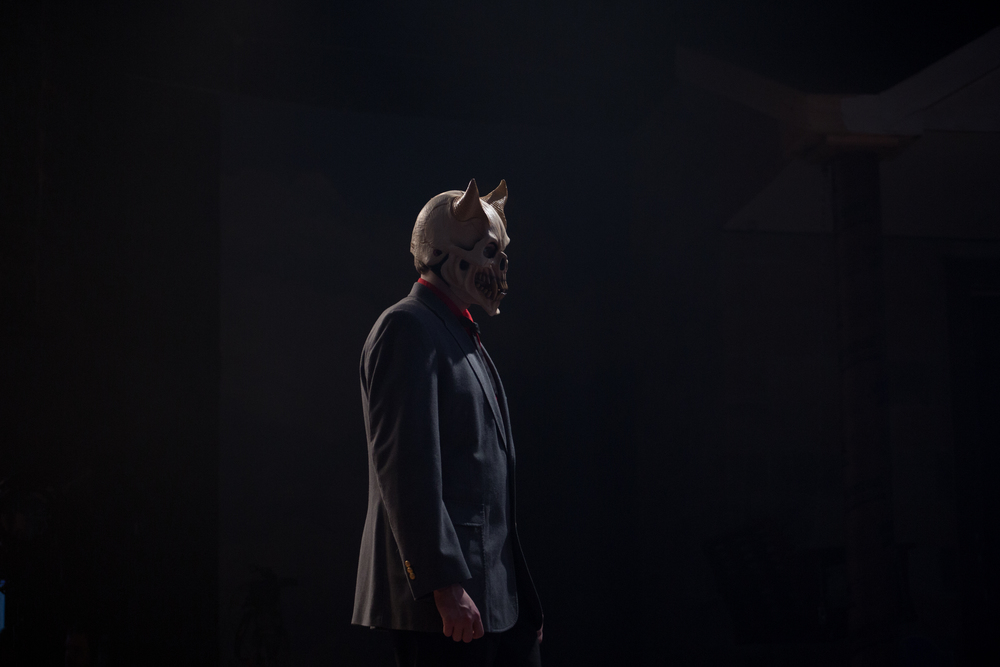

Tom Chandler ’16

In Front of the Lens

By: Grace Gerrish ’15

In the midst of a gaggle of flamboyantly dressed neighbors, Medea (Evy Yergan ’16) looked lost and confused beneath the hot Texas sun. In actuality, the source of the heat is a glaring spotlight—pointed at her by a swarming, omnipresent camera crew. They project her confusion onto two large screens for the entertainment of a studio audience—and an entire community.

In American Medea, a retelling of Euripides’ mythological tale, Medea’s husband, Jason (Jack Mulhern ’16), leaves her for the daughter of Bible-quoting town celebrity, Creon (Chis Naughton ’17). This marital disharmony incites a media circus that calls into question the boundary between Medea’s psychosis and the events of the play, as well as the boundary between the actors and the audience. Meanwhile, Medea deals with the very factual issues of misdirected feminism, the stigmatization of mental illness, and a society steeped in religious teachings about the hellfire that supposedly awaits her.

Hallie Smythe ’17, Keegan Kelly ’17, Sydney Tennant ’17, Alison Schilling ’15

American Medea came to Skidmore’s Janet Kinghorn Bernhard Theater with playwright Holly L. Derr. Of the plays she offered to direct, American Medea was the only one of her own, and department chair Lary Opitz chose it in the hope of offering students a different kind of acting experience. In comparison to recent mainstage productions, American Medea is a comparatively genre-bending and avant-garde piece of theater, giving students a chance to not only interact with a script that veers from theatrical conventions in both style and subject, but to bring their own voices to it as well.

Derr made it clear early on that her script was open to edits, and she encouraged the actors involved in the production to make as many suggestions as they wished. Tom Chandler ’16 did research on the real-life counterpart of his character, Pastor Davidson, and discovered that he often wore a devil’s mask while preaching on street corners and college campuses. A mask was then added to several of his scenes. Madison Caan ’17, who played Medea’s psychiatrist and stand-in for Euripides’ King Aegeas, was interested in the unsettling power dynamics that sometimes prevail in doctor-patient relationships. To reflect this, she suggested making the doctor distinctly sexual, in an effort to purposefully discomfort and exert dominance over the withdrawn and conservative Medea—this new insight was also worked into the script.

Of course, the show changed in more ways than simply the redaction of a line or the addition of a prop or costume. The entire concept of the television studio set was the idea of Artist-in-Residence Garett E. Wilson, whose openness to making such a drastic change to the production speaks, at least in Derr’s mind, to the imaginative power of the Skidmore theater community, and the comfort with which both staff members and students maneuver through the creative process.

Naturally, the change not only drastically recontextualized script, but also provided studentsa chance to experiment with new kinds of lighting and studio cameras.

American Medea at Skidmore College

Scenic designer and Artist-in-Residence Garett E. Wilson was largely responsible for coordinating and directing this camera crew, whose camera work was displayed on two large screens on either side of the stage. Wilson and Derr’s decisions determined issues such as which shot should be displayed on which screen, when the video feed should cut to a different camera, and from what angle and distance each cameraperson should be filming. The two also had to choreograph the movement and placement of these camera people, since they maintained a visible stage presence for the entirety of the show. This choreography was then executed during the show by Kendall Gross ’16. During the department’s post-show critique, students pointed out that the tech crew members were, in many ways, actors as well, especially considering that not only were the camera operators on stage, but the sound booth, lighting crew, and stage management table were in full view as well.

This studio stage also provided additional learning experience for actors interested in working in film or television after graduation. Students in Yvonne Perry’s Acting for the Camera course, particularly Tierney Melia ’15 and Madison Caan ’17, were able to apply the techniques they had learned, but also had to work on subverting some of those lessons as well. Since the production is concerned with the visibility of the cameras, the actors had to learn how to consciously interact with them. Derr said that it was “a fun challenge for [the actors] to figure out how to continue to be theatrical…but also make use of the fact that these cameras are there and a part of the narrative.” Jonathan Lee-Rey ’15, featured most prominently as one of the show’s fast-talking television hosts, summarized how this tension between camera and stage affected his performance: “Things that we got on camera don’t usually read when you’re performing in a theater space,” he pointed out, going on to elaborate how stage work is largely about “listening,” but the camera makes minute gestures such as raising an eyebrow easily conveyed even to audience members in the back row. Evy Yergan ’16 found the camera a bit more difficult to become accustomed to, but felt that this benefited her performance. “[The camera] makes me self-conscious, and I think Medea felt the same way.”

Evy Yergan ’16

Just as this production incorporated many different elements of performance, there were many facets of background information to be explored before the acting or filming even began. Students read the original Euripides and took seminar courses on media theory, Bible study, the psychology of postpartum depression, and psychiatry. Derr found herself wholly impressed with the actors, who completely immersed themselves in the information that makes up the world of American Medea, and fully understood the implications of each issue within the text.

Students also did research on some “real life Medeas,” or real life women who had killed their children out of mental insanity or desperation. A major facet of the production involved incorporating their stories and even their real words into the script, leading to a more nuanced understanding of how a mother, even a mentally ill one, could fathom committing such a crime. For example, Yergan’s haunting 911 call, begging for a police officer to stop her from going through with the brutal murders of her five children, is taken from the actual 911 call of Andrea Yates, the story with which Medea’s story most closely aligns. When the responding officer (Josh Karen ’18), arrives too late and returns to the stage after surveying the crime scene, he despondently recounts the graphic image of one of Medea’s children in the bathtub—the method Yates had used. To the same disturbing effect, Creon’s unsettling closing monologue is taken from the court record of one of the lawyers who presided over Yates’ trial. This cool and matter-of-fact monologue reinforced society’s incredible misunderstanding of the mentally ill, even in such tragic cases as Medea’s. Though the audience is not directly informed of any of these instances of real life connections, the words speak for themselves, building on the overwhelming sense of discomfort that pervades even during the play’s frequent moments of comedy.

Derr calls the Skidmore Theater Department “fearless” in its pursuit of unravelling this complicated text. “Professional actors come in and learn their lines,” she says of her previous work, but “it was refreshing to have students who are engaged and say, ‘I really want to get this.’” Most importantly, she found Skidmore students’ desire to engage with any material, from traditional musical to unconventional performance, the most admirable. “Cabaret did Spelling Bee, and then we had Dancing at Lughnasa and American Medea in the same season. Skidmore is really eclectic, and I love that.” Once again, the Skidmore Theater Department has taken creativity and ingenuity to a whole new level, and extended itself to face challenges both on the stage, and in the fragile mind of this American Medea.

Lindsay Nuckel ’17

This article originally appeared in print in the Fall 2014 Skidmore Theater Newsletter.