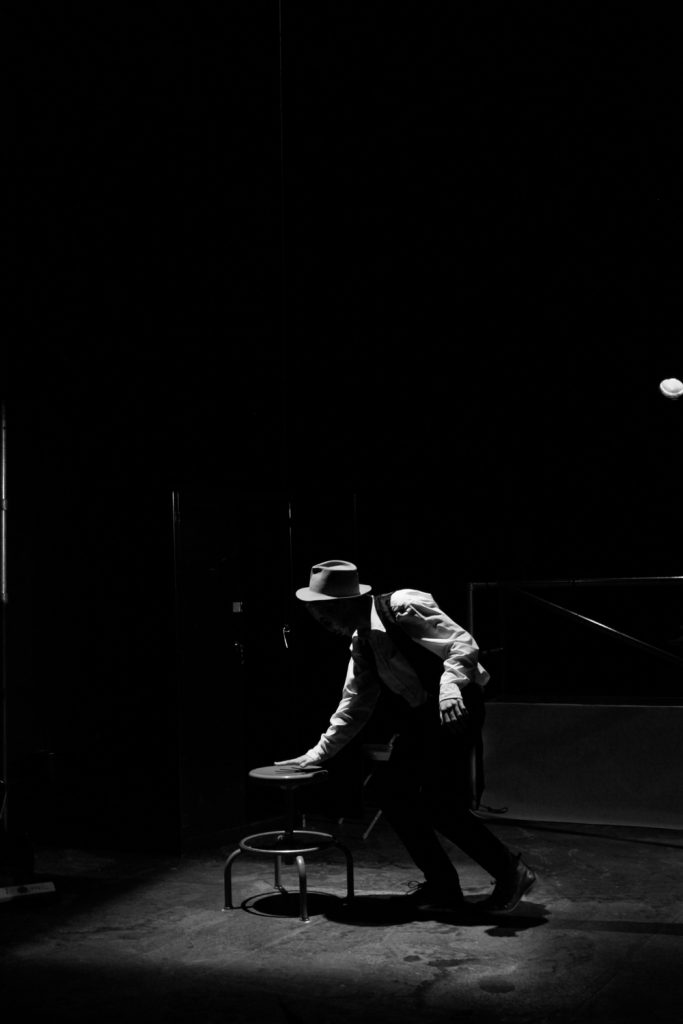

Shea Leavis ’17 (Kaspar) and Lindsay Nuckel ’17 (Prompter)

SCHREUER ’16:

On the surface Peter Handke’s Kaspar seems to be a play about teaching someone to speak. But it is far more than that, because language is not just a communicative technique. Language constructs how we view the world, how we perceive it, the relationship between things, and our relationship to things. Language determines how the outside world perceives us and how we perceive it. When language has such a powerful role in life, to learn it is to learn a new way of seeing the world.

Kaspar’s socialization, through the learning of language, is imparted by the prompters’ voices, which could be either embodied or otherwise. These prompters perpetually command Kaspar. Their teachings are not just innocuous table manners or sweeping techniques. The prompters also ingrain cultures values into Kaspar by saying that everyone must work hard, that war is good, and that you can torture to get the information you need. They say these things like they as obvious as table settings, not differentiating between that which should be personally-decided opinion and that which should be social fact.

As he is learning language and the culture that it entails, Kaspar cannot resist these ideological points; his only choice is to learn them as if they were facts because he has never been shown the difference. He will learn that war is good and set a table one in the same. Paramount in both Kaspar and America’s neo-liberal ideology, which this piece heavily critiques, is the idea of choice. Kaspar is on multiple occasions told not that he can choose but that he must choose. But what choice is left to him? He was forced into assimilating to the prompters’ language, their worldview: he is told how he must think, act at a table, and view political issues. He is being primed for a society that bases itself on the idea that we are individual and have the right to choose we will be, but this is exactly what is denied to Kaspar.

(From left) Becca Gracey ’18 (Prompter), Julianna Quiroz ’17 (Prompter), and Shea Leavis ’17 (Kaspar)

Kaspar is forced into a self and language built by the prompters and their culture. Kaspar is not just learning a language, he is being recreated, molded, shaped by the language he is learning– a language he did not choose. To build a new Kaspar, the old one must be destroyed. This is what the prompters attempt to hide: they want their audience to believe that their actions are constructive, educational. But inherent in the creation of something new is the destruction of what was there before– the being Kaspar was once. Even if one perceives that being as language-less, primitive, not deserving of the same dignity that we would grant to those that know and speak as we do, they must admit that Kaspar was a person. But the self that Kaspar was is splintered and destroyed, ripped apart into various pieces. The forced assimilation that Kaspar undergoes is violence at its most wretched. It is not attacking the body, it is attacking the mind, the self. It destroys Kaspar, just not his physical form. The shell that is left, Kaspar’s physical form, is filled with something new. He is no longer Kaspar but instead a golem– an edifice to be stuffed with the ideology of the voices.

The play’s culminating moments, featuring multiple iterations of Kaspar and Lindsay Nuckel ’17 as Prompter.

Kaspar is not just the story of a boy from the wilderness being socialized but is also representative of humanity’s development of society. This is not the first time this story has been told– it echoes the theories of 18th century philosopher Jacque Jean Rousseau. Rousseau believed that one could not understand human nature by looking at people as they currently exist because they are so shaped by their culture. He critiqued his contemporaries for failing to consider humans outside of European social constructs, claiming that such analysis says far more about European culture than universal human nature. To express his theories, Rousseau writes a narrative account of humans’ pre-societal, natural existence and their creation of society.

Kaspar’s state at the beginning of the play is akin to a Rousseauian conception of pre-social humans. They are solitary, wild, and language-less. Rousseau would add that Kaspar and these people were content in the natural world, their desires in line with their means to achieve them, without the ever-driving want that keeps modern people from happiness. Just as Kaspar’s interactions with other humans lead to his capture and removal from nature, basic interactions led people out of their natural state of contentment. This crux of Rousseau’s theory is expressed perfectly in Kaspar’s line, “but falling is twice as bad ever since I know that one can speak about my falling.” Rousseau himself writes, “whoever sang or danced best, whoever was the handsomest came to be of most consideration; and this was the first step towards inequality, and at the same time towards vice.” Here both Kaspar and Rousseau are saying that once in society, people are subject to the opinions of others; they are told it is wrong to break social custom– in Kaspar’s case not looking foolish by losing balance– and to feel bad if they do. In the reverse, people are revered for excelling in that which society values and therefore people desire to fulfill their social expectations. Rousseau believes that the drive for others to think well of us corrupts humanity, for it engenders jealously and hatred, conflict over opinion and money. This is the root of our unequal society, in which those with more resources fight to grow ever more powerful, while those who society deems less valuable suffer. (It seems that with money’s control over our society, the traits valued most are being born rich and one’s ability to screw over others in business). Competitive striving for social acknowledgement breaks the cycle of human contentment found in the state of nature. This is exactly what Kaspar is subjected to. He unwillingly internalizes the pain and pleasure related to how society views his actions, and he is forced to act not as he desires but as society desires.

Shea Leavis ’17 (Kaspar)

The play Kaspar is a social commentary on the subtle ways that society teaches its members to conform and constructs the meaning in the world around them. Kaspar is never given the freedom to think for himself; nothing he does is his decision; everything he learns he is told he must do. He is instructed to choose but everything he is told by the prompter is a must. The most important but unspoken “must” of all is he must listen to the voices. This is the most absolute “must” in society. One must acquiesce to social rules or be scorned and considered to belong in the very wild from which Kaspar emerged.

Kaspar’s brutal education does not make him a person, just as society does not define what is human. It instead destroys him; he becomes a vessel that can repeat musts into a microphone– a vessel that wishes he was a person “like somebody else was once, like he was once”. At the conclusion of the play, every part of the fractured Kaspar makes this wish, while the most constant aspect of Kaspar spews an accumulation of “musts” being broadcasted into his ear by a prompter. This lays bare the conflict that exists within all of us, the struggle between the “musts” taught to us by society and our desire to realize the person we believe ourselves to be or to have been.

Jack Schreuer is a blogger for the Skidmore Theater Living Newsletter.