Photo: Sue Kessler

Fake News and Real Mobs: Julius Caesar

By Kallan Dana

It’s not about Caesar.

This much is clear. He gives the play its title, certainly, and the sound of his name reverberates across the stage for the entirety of Lary Opitz’s ninety-minute production. Every character who speaks the two-syllables does so with clear intent: celebrating, decrying, eviscerating, honoring, respecting. But Julius Caesar (Atticus Rego ’21) barely appears onstage before his murder, taking up no more stage time than any of the other Roman citizens. His name carries weight, but Julius Caesar is not what Julius Caesar is about.

If not Caesar, then, who, is this play about? In his time-defying adaptation of Shakespeare’s classic tragedy, Opitz offers several alternatives. Perhaps Cassius (Graham Cook ’19) and Brutus (Nick Leonard ’20) are the centerpieces. It is these two, after all, that lead the conspirators in their killing of Caesar and these two that tragically commit consecutive suicides in the final moments of the play. Another possibility, then, is Mark Antony (Ziggy Schulting ’18), Caesar’s loyal confidant, who uses her companion’s murder to catapult Rome’s citizens into riotous outcry.

Photo: Sue Kessler

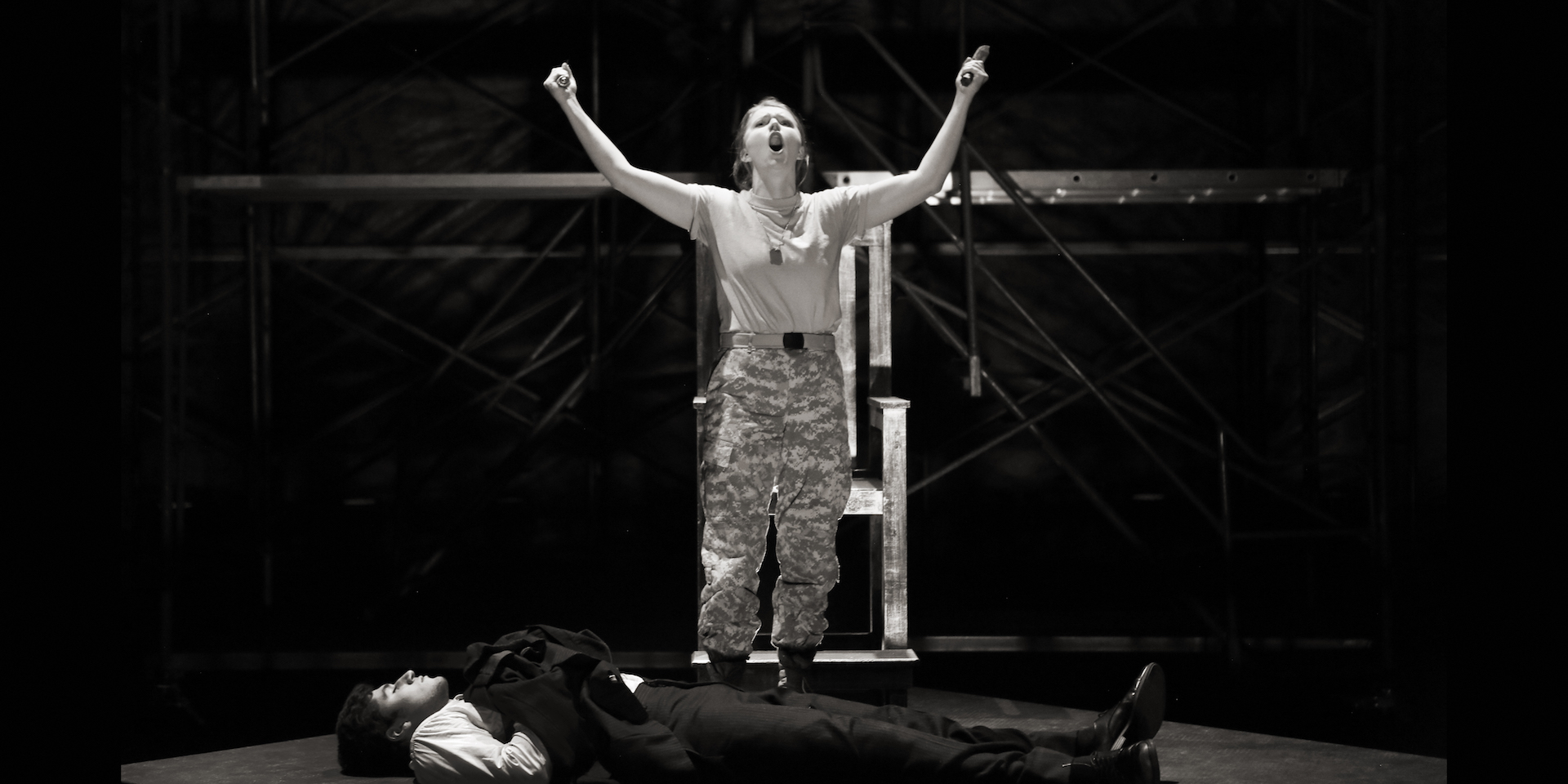

These pivotal moments, Caesar’s death, Antony’s speech, Cassius and Brutus’ suicides, may initially seem to be the central dramatic events of the play, but Opitz frames it otherwise, instead centering the entire production around the outraged, raucous citizens’ misguided murder of Cinna the Poet (Matt Clyne ’20). The mob of Roman citizens’ harassment, attack, and murder of the innocent Cinna is presented in violent detail. In this production, Cinna’s death surpasses in length Caesar’s, and the brutality is extensive—the crowd kicks him down, drags him across the ground, beats him with bats, breaks his fingers one-by-one, and leaves him writhing for several excruciating seconds before finally twisting his neck and ending his suffering. It is in this lengthy death scene that Opitz’s answer to the question of Julius Caesar’s meaning becomes clear; it is not a show about any singular person but rather it is about what drives us, collectively, to violence. Rendered in sharp, eerie darkness, shadow, and bursts of color by lighting designer Chloe Brush ’18, the violent sequences of the play seem both fully entrenched in realism, and also removed from it—a visual representation of the inhumane evil in harming the helpless.

The mob, consequently, is ever-present. It fills up scenic designer Jared Klein’s wide, cavernous playing space. Climbing on scaffolding, crowding the center, running into the aisles, and sitting in the theater’s house, the crowd of citizens drags the viewers into its lived experience. While Antony is the sole person onstage for several minutes, rousing the crowd, the citizens still sit beside the audience, cheering or booing into our own ears, and consequently making us complicit in their actions. Costume designers Patty Pawliczak and Omi Furst ’18 have smartly dressed these characters so that, aside from their Elizabethan turn of phrase, they appear virtually the same as us. They look like our coworkers, our friends, our parents, ourselves. It becomes increasingly hard to disentangle performer from spectator, even as increasingly violent acts occurring onstage. Even when they are offstage, we often continue to hear the crowd’s aggressive cries in our ear, as sound designer August Sylvester ’20 plunges us into a world of unrelenting cruelty.

Photo: Sue Kessler

Opitz’s production is adaptation, and consequently he has taken liberties with the structure and rules of the world of the play. Most notably, the entirety of the action is narrated by and commented on by a removed newscaster (Killian Grider ’18), never seen in person, but rather viewed on parallel monitors on either side of the stage. His presence drops us directly into the present-day American experience. The newscaster’s modern vernacular—entirely Opitz-penned text— melds together three different times synchronically: ancient Rome (the setting of the events), Elizabethan England (the setting of Shakespeare’s language), and the modern United States (the setting of the adaptation’s characters and Opitz’s words). In this way, the newscaster both brings us closer to contemporary American politics, and the controversy surrounding news and media rhetoric, while also drawing us further away from the analogues of Caesar to ourselves. Brechtian scene descriptions, also projected onscreen, heighten this distance—we can only become so immersed in the story before being reminded that it is just that, a story, and one with a message.

Opitz is willing to drive home the message, introducing a new theatrical convention, also Brechtian, in the final moment of the production. After Brutus has killed himself and Octavius has taken the throne, the lights fade. It appears that the play is over, and then, suddenly, the entire company emerges once more, accompanied by light and music. They stand in lines and sing to us directly, as candid and direct as the newscaster had been in his reporting. The bodies of the actors, now detached from the characters that had once inhabited them, recount the events of the play, posit questions about what has happened, express doubt for what is to come. In the standout line of the song, the chorus of sixteen bellow: “Fake news they cry!/Though it’s a lie.” It’s a line equal parts inflammatory, surprising, funny, and saddening. Above all else, it shows Opitz’s grasp of the traditions of political theater—this is a production meant to make us reflect on ourselves and our world, so that we may choose to take action.

Photo: Sue Kessler

Or, perhaps, no action will be taken at all. The newscaster’s final exit cast poses similar questions to the song; “Will our democracy survive?” he asks, but before that, “Will Octavius become another Caesar?”

Julius Caesar, just like our own world, is a play dominated by the rulings of men. Caesar is a male populist, Cassius and Brutus are the men who lead his demise, and Octavius is his eventual successor. Mark Antony, in this particular adaptation, a woman, stands by Caesar’s side in the beginning and by Octavius’s in the end. Though she has her moment of control, Antony is still relegated to being a woman behind a man. The soothsayer (Anabel Milton ’18) who tries, unsuccessfully, to warn Caesar of his impending murder on the Ides of March, is ignored, regarded as mad. In Portia (Annabelle Vaës ’19) and Calpurnia (Becca Gracey ’18), Brutus and Caesar’s wives, respectively, we see two women who express concern for their husbands, for their futures, and are brushed aside for the power-driven desires of men.

Photo: Sue Kessler

In this adaptation, the men remain firmly, solidly in charge, as ever. It’s appropriate. If Opitz’s production of Julius Caesar is meant to mirror our own world, what better way than to show the timelessness, not only of mob mentality and governmental corruption, but of the gendered power dynamics that plagued Roman citizens then, and continue to plague us now. It’s not about Caesar, it’s not about Trump, it’s not about any one man or person at all. It is about us; what we do to fight demagoguery, and systemic prejudice, and what allows us to become complicit in it.

PHOTO GALLERY

PRODUCTION CREDITS

By: William Shakespeare

Adapted and Directed by: Lary Opitz

Scenic/Video Designer: Jared Klein

Sound Design: August Sylvester

Lighting Design: Chloe Brush

Costume Design: Omi Furst, Patricia Pawliczak

Fight Choreography: Douglas Seldin

Music Direction: Killian Grider

Hair and Makeup: Megan Muratore

Choreography: Barbara Opitz

Cast: Matt Clyne ’20 (Murellus/Cinna The Poet/Pindarus), Kat Collin ’21 (Lucius, Citizen 2), Graham Cook ’19 (Cassius), Ethan Embry ’19 (Flavius, Trebonius, Citizen 3, Messala), Kyle Ferris ’18 (Guard, Metellus, Citizen 1, Octavius), Rebecca Gracey ’18 (Calpurnia, Lepidus, Antony’s Soldier), Killian Grider ’18 (Newscaster), Rowen Halpin ’19 (Cobbler, Photographer, Publius, Citizen 4), Jacob Hudson ’18 (Guard/Cinna/Antony’s Soldier/Citizen 5), Olivia Iannotti ’18 (Carpenter/Popilius/Citizen 6), Mira Lamson-Klein ’18 (Decius), Nick Leonard ’20 (Brutus), Anabel Milton ’18 (Soothsayer, Ligarius, Titinius), Anthony Nikitopoulos ’21 (Casca, Strato), Atticus Rego ’21 (Julius Caesar), Ziggy Schulting ’18 (Mark Antony), Annabelle Vaes ’19 (Portia, Antony’s Servant, Volumnius, Citizen)

Crew: Jared Klein (Technical Director), James Varkala (Assistant Technical Director), Jessica Thomas (Scenic Artist & Technical Assistant), Zoe Lesser ’19 (Assistant Director), Philip Merrick ’19 (Assistant Director), Emily Hardy ’21 (Assistant Stage Manager), Taylor Jaskula ’21 (Assistant Stage Manager), Katie Jacobsen ’18 (Dramaturg), Jessie Blackman ’20 (Props Master), Jessica Thomas (Paint Charge), Ella Long ’20 (Wardrobe Head), Leah Mirani ’18 (Wardrobe Head), Max Helburn ’18 (Master Electrician), Max Clifford ’21 (Assistant Master Electrician), Brandon Young ’20 (Light Board Operator), Lily deButts ’21 (Sound Board Operator)

***

Kallan Dana is a Junior Theater/English Major and Staff Writer for STLN