The design team of “Men on Boats.” Left to right: Wynn Lee ’21 (Props Master), Jessie Hamilton ’20 (Sound Designer), Romi Moors ’19 (Scenic Designer), Lea Tanenbaum ’19 (Lighting Designer), L. Esther Hibbs ’20 (Hair Designer), Julia Guy ’19 (Costume Designer). Photo: Hanna Yurfest ’21

By Em Miller

None of the roles in Jaclyn Backhaus’s Men on Boats are performed by cis, white men. Instead, the actors have any sort of other intersection of identities. In this production, directed by Nina Slowinski ’19, the entire design team is similarly comprised of students who identify as anything other than cis, white men. Em Miller ’19 went behind the scenes to speak with most of the designers about their work on this production.

The first thing scenic designer Romi Moors ’19 did after reading the script for Jaclyn Backhaus’ Men On Boats was make a list of things that could be used as boats. Her reasoning for this comes from a desire to doubly subvert the play’s ironic title, even more so than what the casting notes call for. “There aren’t a lot of men, so I didn’t think that there had to be boats,” she explains.

Ultimately, instead of boats, Moors opted for ten brightly colored tire swings hanging in the center of the stage, and instead of the white men who populated the 1869 U.S. expedition through the Grand Canyon, director Nina Slowinski ’19 cast an ensemble of cisgender women, transgender and gender-nonconforming actors, and people of color. Backhaus’ play is a tongue-in-cheek look at the masculinity and imperialism of American stories about Manifest Destiny. As costume designer Julia Guy ’19 puts it, “This is a show for everyone who was not included in all of the histories we learned in grade school.” It follows an expedition led by Major John Wesley Powell (Emily Cross ’19) that was the first group of white explorers to travel the entire length of the Grand Canyon, and tracks their dynamics as they contend with a landscape that is unfamiliar to them and with the ramifications of their exploration. They struggle to build camaraderie, leave a mark on the frontier, and simply survive the wilderness.

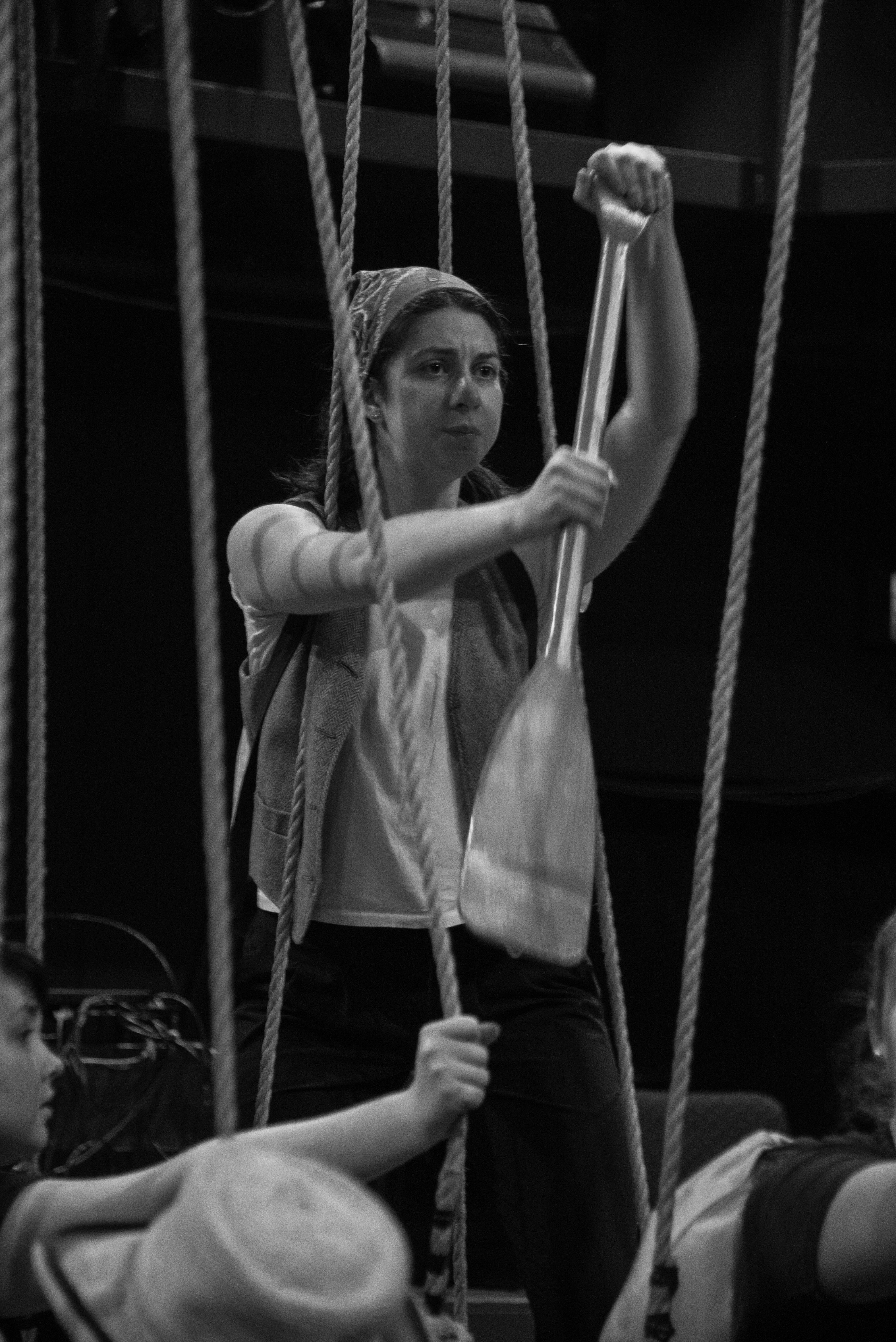

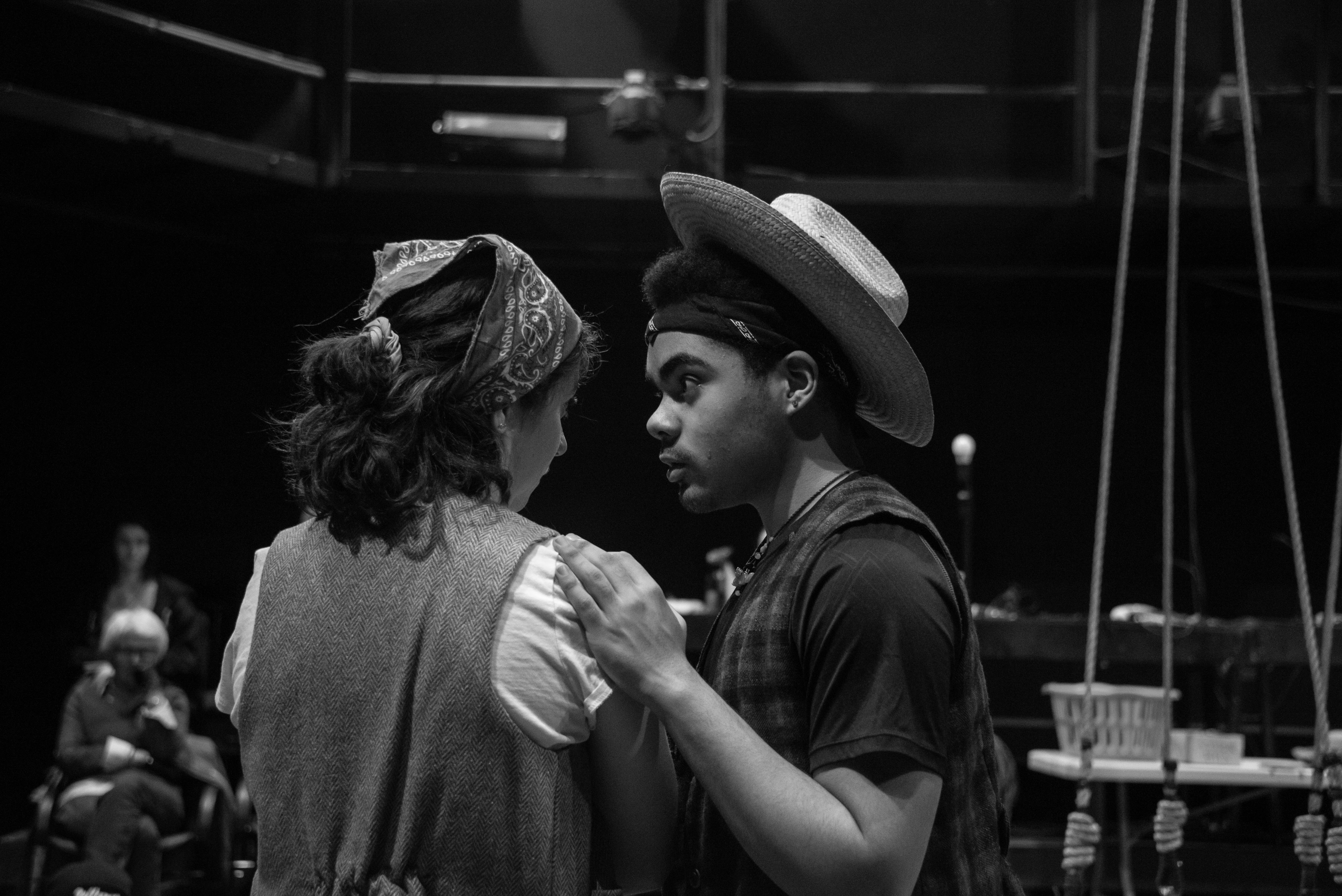

Photo: Max Lowe ’19

Backhaus is by no means the first playwright to reframe stories that traditionally center white men by casting marginalized people in the major roles, but her choice of original narrative is particularly interesting. “One thing that I did think about is: Why did she choose to connect these two worlds, these worlds of 1800s frontiersmen and marginalized people?” Moors asks. “And I think one of the connections I draw is a motivation to not do what is necessarily expected, but instead a desire to go outside of that. The people who went to the frontier, they could’ve stayed home. But they had this impulse to go out and do this very, very dangerous thing that was completely unknown. […] It’s about people who are choosing to do things outside of what is expected, and being bolder than perhaps what they are being told to be.” Just as the frontiersmen navigate and make visible the boundaries of the United States, so too do the marginalized people in the cast navigate the boundaries of acceptable and unacceptable manifestations of gender and race. Importantly, they are mapping these delineations simply by being visible as themselves. “No one in this show is ‘passing’ as anything,” Guy says. “It is not a show where women and non-binary people are dressed up as men.”

Hair designer L. Esther Hibbs ’20 was similarly eager to blur the lines of the gender binary in her own work. “Being outdoorsy and rugged are qualities that are stereotypically ‘manly,” she says. “I was interested in using hair to add the feminine to those qualities.” She looked to braided hairstyles that communicate both functionality and femininity. She was further inspired by Guy’s impulse to empower the actors in terms of their costume design and it informed how she structured her own design process. “Instead of developing one style for each person, I came up with a catalogue of hairstyles and tools they could mix and match,” she explains. Hibbs even led the cast in workshops where she collaborated with the performers on finding unique styles for their characters, developing what she calls a “partnership” between designer and actor. “It’s been really gratifying to work together instead of telling them what to do,” she adds.

Photo: Max Lowe ’19

This is a play with a grander scope than can easily be represented at the scale of the Black Box. Moors, originally daunted by the nearly cinematic stipulations of the text, sees the setting as an exciting challenge: “There are certain sets that you can do as written, like A Doll’s House, but this set you can’t do as written. You can’t take anyone to the canyon of the 1800s, you have to make an abstraction, and that’s part of the genius of the writing—she forces the designers to make an abstraction, because you cannot possibly make it a reality.” The show’s comedic tone informs the playfulness of these abstractions, such as the tire swings that stand in for boats, or the meandering lines of orange and cyan paint that represent the river. Bright colors, inspired by the scenery of the Grand Canyon itself, are a central part not only of the set, but also the lighting design. Lea Tanenbaum ’19 is also excited about what she refers to as a form of surrealism in the show, and tells me, “I’m using colors that I wouldn’t normally use and at a saturation I wouldn’t normally use. I’m not just using a blue, I’m using the deepest blue that I could find.” She also notes that the play is not one that requires perfectly naturalistic lighting that matches up with the time of day and location of the expedition in the canyon, but instead is better served by lighting that tracks the progression of tone as the explorers’ situation changes.

Sound designer Jessie Hamilton ’20 has a slightly different perspective on this abstraction, and they state, “It’s been an ongoing question of, ‘in a world where boats are tires, what does water sound like?’ Of all the design elements, I think sound veers towards being the most realistic, but then at the same time, there are a lot of moments where it breaks out of that realism—we’ve been talking about giving the boats theme songs.” With respect to costuming, Guy adds, “I really wanted to focus on highlighting the comedic aspect of the show. I started out very historical, but as the process has gone on, I have moved into a more stylized design.” It is evident that every designer is excited about the opportunity to work on a play with such a lighthearted tone, even as it deals with the serious topics of imperialism and patriarchy.

Photo: Max Lowe ’19

Another unique task for some of the designers is how the show is an active one in many ways, not the least of which is the ever-swinging group of tires. “I’ve been trying to think of it as lighting a dance,” Tanenbaum says. “Because when you’re lighting a dance, you want it to be more sculptural, and it’s not so much about what they’re saying and always more about the emotion and what they’re physically doing. It’s allowed me to put lights in places that I might not otherwise put them in order to try and highlight the form of the body.”

“Making rapids? Not just rapids, the characters traveling down rapids?” Hamilton laughs when I ask them about the challenges of doing sound design for this particular play. “It’s hard because it’s not just having a water sound, you have to make it sound like they are passing effects, it’s so consuming—that’s a terrifying prospect to design and build, but at the same time… to be able to stand in the middle of the room and feel what that sounds like after you solve the problem is a really satisfying thing.”

Photo: Max Lowe ’19

The play’s power also comes from its critique of mainstream American narratives of history. As well as poking fun at the way the explorers obsess over their masculinity and presumptuously name the landmarks they pass, Backhaus also reverses the stereotyped relationship between indigenous Americans and white settlers in an interaction with members of the Ute tribe, portrayed by Marina Kalaw ’22 and Tatsuya Rivera ’22. “I’m a big fan of the patronizing tone [Kalaw and Rivera] have throughout that scene,” says Hamilton. “I think a lot of the historical critique exists in the play’s use of irony and sarcasm, and I think that needs to be played right for it to come across. There are definitely ways where the Ute tribe could be played very badly, and an entirely different message could come across from that scene, and so I think Nina has done a really good job with those moments. It’s evident that the entire cast is aware of that context and that it’s being discussed from the start.”

Although it may sound at first like a daunting task to capture both this serious criticism and the show’s tongue-in-cheek tone, this production’s creative team has risen to the challenge.

Photo: Max Lowe ’19

*

All interviews were conducted and transcribed by Em Miller ’20, with the exception of Esther Hibbs’s interview, which was conducted by Philip Merrick ’19. Kallan Dana ’19 transcribed the interview and consolidated her words into this article.

*

Men on Boats opens Friday, March 1st and runs through Thursday, March 7th. All shows will be at 8PM except for the 2PM matinee on Saturday. To purchase tickets, click here.

*

Em Miller is a junior staff writer for The Living Newsletter.