BY MAX MCGUIRE ’24

On March 1st, I sat down a couple of hours before the interview, stressing over questions to ask and worrying about what to do if I ran out of things to say. However, I find that I love engaging in interviews because they end up becoming lovely conversations about peoples’ life experiences and work. As soon as I sat down in her office, my nerves calmed and I knew that it would be an honor and privilege to interview someone with as much experience as Aniko Szucs does in both the theatre and academia. What follows is a transcription of an hour-long conversation (cut down for your convenience).

Me: Just to begin, state your name, your background, where you are from, what got you into performance studies and dramaturgy…

Aniko: “My name is Aniko Szucs, and… At this point, most of the department knows I’m from Budapest, Hungary. A fun fact about me is that I always wanted to be a dramaturg. I remember telling my mom as a teenager, ‘I’m going to be a dramaturg,’ and my mother just stared at me dubiously, like, ‘Fine, but what is that?’ I came from a middle-class-ish family. My father is a journalist, my mother is a doctor, and they both wondered what a dramaturg might be. But I fell in love with the theater, just as I fell in love with research, and I really wanted to pursue a career in the theater. To this day, I think it’s the most mesmerizing experience, taking a script, a two-dimensional dialogue, and building a unique, beautiful, immersive world we all are part of.

I never wanted to be an actress because I had horrible stage fright. At the same time, I was always very interested in dramatic texts as they perform—and as they are being performed—on stage. Further, I also thought that I was a gifted collaborator. I aspired to be a thoughtful and empathetic collaborator who would be an essential team member. Someone, who sees the production in its totality, considers the many little parts as they come together, and notices if they don’t, and someone who brings the kind of knowledge to the rehearsal room that is super-useful for everyone. I was lucky to be born in a country where theaters had positions for this niche job. I knew I wanted to pursue this, and I was fortunate to have gotten opportunities at the beginning of my career. By the time I was 23 years old, I had a full-time job as a resident dramaturg in one of the most prominent theaters in Budapest”.

Me: Wow! That’s awesome!

Aniko: “Yes, yes, it was, but the price that I paid was that by the time I was 27, I was quite disillusioned, I would have to say. Speaking about the context of the United States, I truly wish the state here would provide more support to the artists. I greatly respect artists here as they pave their paths. Artists are some of the most resilient and wonderful people for that reason. In Hungary, though, at that time, the state still provided a safe income for many artists, and somehow, as a result, the company I worked for, got very comfortable. There was a lack of urgency. I want to emphasize that I am very much against the myth that only the starving, precarious artist can create great art. Still, in this environment, perhaps due to the postcommunist legacy, the comfort and entitlement resulted in mediocracy and toxicity. This was an uninspiring environment, with lots of drama, as many famous actors worked there. And I felt that I only love drama so long as it stays on the stage.”

Aniko: There was a discrepancy between the quality of our work and what we thought of ourselves. Meanwhile, I read more and more about Performance Studies. There was this one little book by Richard Schechner, “Performance,” translated into Hungarian. Reading it, I felt inspired, and it made me think about some of the essential questions surrounding artmaking. These are such cliché questions, yet they are so important: how do we make this world better through our artistic practices? Can we make art that will be a social or political intervention? And even if it won’t be, can we at least aspire to create such work? Are we ambitious enough to do this work? At that theater company, we weren’t. In performance studies, though, these are the questions that drive our inquiries, so I decided to apply for the graduate program at New York University.

Me: “I think that all these things that you are talking about- a collaboration with other artists, and then, how as an artist or a dramaturg, or whoever you are, working in the theatre world- how does your art make life better? And you say it’s cliché, but it is really the goal. You’re thinking like, ‘what is my work- my art, going to leave behind’- or I think about that anyways, a lot, with my own art. What is the impression I’m making on the people around me; what is the impression I’m making on the world around me with my art? With that being said, I was doing a little research, and I was looking at the Yale website, and it said that your research interests include ‘political performance and surveillance, post-communism, memory politics, and genealogies of dissidence and resistance in Central and Eastern Europe’. My question is how has your research shaped your theatre career and journey, or vice versa?”

Aniko: “Oh, that’s such a good question. I am extremely, extremely interested in theatre that aspires to be political. What we mean by that, or how is theatre political- that’s what we interrogate for 14 weeks in our “Theater and Culture” class. *laughter*

Me: “Right”. *laughing as well because I took Theater and Culture II with Professor Szucs*

Aniko: “On the simplest level, I want to discuss plays that do political work, the political work of interrogating representation. Highlighting social injustices and exploring how different forms of oppressive structures and institutions affect us. Theatre can capture these embodied experiences, perhaps even without words. Theater is a space of potentiality, not only for telling stories but also for creating communities and forging solidarities. These experiences are all political. We are essentially political beings, especially in the rather radicalized societies we live in”.

Aniko: “So, to return to your question, how do theory and praxis intersect? I am looking to better understand the nature of the politics in the theater—through my research and teaching and recently through working with a pro-democracy NGO that creates artivist projects. I more and more felt that I had to do this work witnessing the democratic backslide happening in Central and Eastern Europe, and especially in my very messed up home country. I’m extremely wary of nationalist ideologies, but my only passport is a Hungarian one. That’s where my roots are. So when you realize that your country’s leaders are besties with some of the harshest dictators today—that these are our “new friends” in the Central and Eastern European region—you start to wonder about that cliché question: how can I make a difference? How can my art affect certain realities?

Aniko: “So during COVID, while I was stuck there, things got terrible in many East and Central European countries: Poland had its total abortion ban moment, Hungary was in an authoritarian state of emergency, and Belarus after its last free elections became a total dictatorship. I more and more engaged with some very powerful transnational feminist protest movements, and I also joined one NGO. Together we applied for some EU funds and created some ‘artivist’ pro-democracy short films. It was a learning process, I would say. We worked with a group of international artists, and I hope to continue to do that on some level. At the same time, looking at what has happened since then, it feels like we failed.”

Me: “You say like, ‘oh we failed,’ but you still kept creating. You’re still here. You’re still creating. You’re still doing your work. No, did you change the entire politics of a country with a short film? Maybe not, but you made a difference, and you’re still creating in the wake of that. I think that’s very powerful.

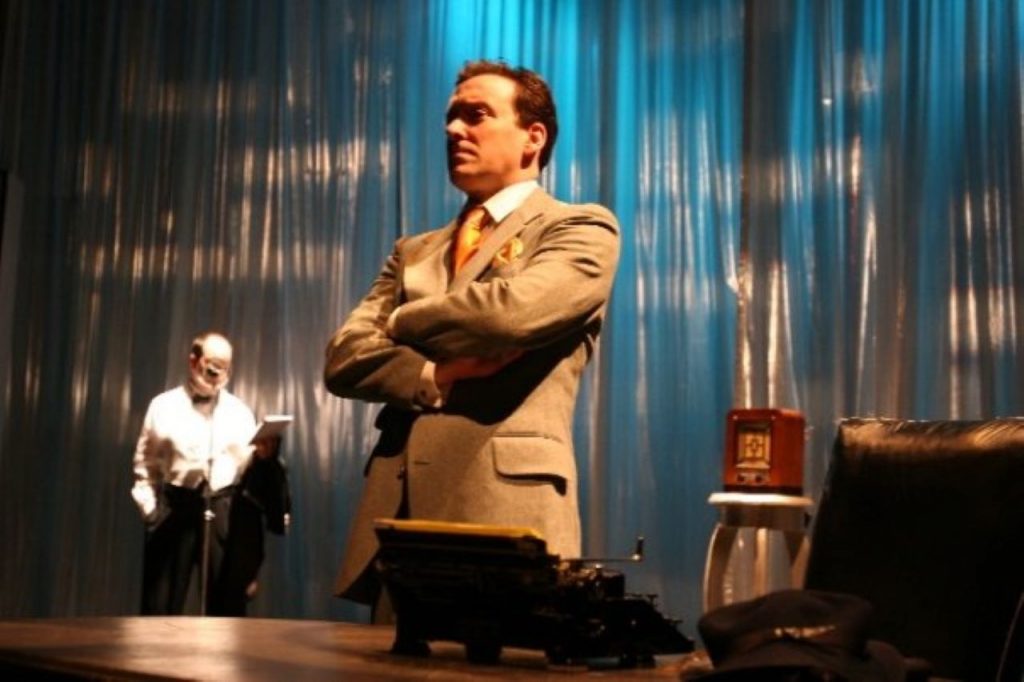

Aniko: “What bothers me is that we worked so hard, and yet we could not prevent the reelection—or the stealing of the elections—of some very powerful and extremely corrupt men. This bothers me a lot. Where I come from, artists often say, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t do politics.’ You can observe something similar in this country, too, as so many artists here don’t want to take a political stand either because if they do, they might exclude some of their audiences. It’s much easier to say, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t engage in politics.’ Yes. Now, with that being said, this raises an important question for artists: ‘what are the different art forms or forms of expression through which I can engage with the political?’ If you put it this way- ‘engage with the political,’ you emphasize that the ‘political’ is not the same as ‘politics’—specifically party politics. It’s more of a larger philosophical aesthetic. It has more depth to it. That’s a question we have to ask ourselves. When we think about some of the performances here (at Skidmore), none are overtly political. Do they address important social and political issues? Absolutely. At the same time, how subtly or overtly they address political issues, that’s a choice the artists have to make. I’m quite interested in the options for artists who want to do it more overtly. For example, The Great Impresario Boris Lermontov Would Like to Invite You to Dinner (directed by Micha Pflam ‘23)…”

Me: “It is a very political piece because it talks about- even though it’s a very specific story and also very absurdist-”

Aniko: “These plays at the department ALL engage with politics. As artists, I don’t think we should always be explicitly, didactically political, except for certain cases when we feel it’s absolutely necessary. But in general, I think the political in the theater is different from ‘artivism’; it is different from the performativity of direct political art action. And I also think Lermontov is a good example because it is political in the best sense. It’s not didactic, you know, it’s not going to push this-”

Me: “It’s not in your face.”

Aniko: “Exactly, but there are so many layers”.

Me: “And you can understand those layers as you unpack the play, and I feel like especially dramaturgy helps with that, and I can see why you’re interested in dramaturgy because it’s like- ‘alright, I’m not a performer, but I really love unpacking plays because there’s so much to unpack here’.

Aniko: “And (Lermontov) is such a good play for complex political theater. At a certain point, however, as an artist, you may realize that you just need to do something that will reach many people. So that’s why we applied for a big EU grant. And when we got the grant, suddenly, we had to work from our aesthetic, our way of thinking and productivity, our identities as artists, and to make a collection of short films for YouTube. And this genre would have needed very different aesthetics. So when I say that we failed, we didn’t only fail because we couldn’t prevent anything, the election system is as flawed as it was in Hungary, Serbia, and North Macedonia, but because we tried to compromise our aesthetics as we were working on the short films.

Me: “My next question kind of goes along with this, and I definitely think you’ve been speaking to this all along, but in the beginning of the interview, you were like ‘I told my parents at sixteen that I wanted to be a dramaturg’ and they were like ‘Okay, what is that? I very much feel like when I first came to Skidmore, Theater Department Chair Lisa Jackson-Schebetta was the first person to introduce me to the term ‘dramaturgy’, and the art of dramaturgy. I had never heard of it before in high school. For students who want to go into dramaturgy, or for people who don’t know what it is, can you speak a little about the value of dramaturgy? Why is it so important in theatre?”

Aniko: “I divide the dramaturg’s work into three different areas: production, literary management, and new play development. I will start with production dramaturgy. Here in the US, the main task of a production dramaturg is to conduct extensive research for the play and put together the actors’ pockets. At the same time, if you have a great collaborative relationship with the director, and this is the only reason you should work together, you are a creative partner in the rehearsal room, too. Where I come from, dramaturgs have even greater responsibilities in production. Since we speak a language almost no one else says, many plays we produce are in translation. Translation is interpretation, as we know. So one of the main reasons we need dramaturgs over there is because most texts inevitably go through a transformation before they are performed. Most of the plays produced in the US were written in English. You hardly ever see translations on Broadway. It’s super-interesting to look at the US theater scene today, NYC and regional, and see how many non-English language plays are being performed in translation. So here, it is different. The greatest advantage of a translation is that you can—and you kind of need to—refresh it repeatedly. In Hungary, some dramaturgs and translators would say there should be a new translation of a Shakespeare or Chekhov play every decade. Through this translation work, we ensure that the language is contemporary, and we start to adapt the play to the social-political reality of the present. Usually, the final draft of a script is the result of a very close collaboration between a translator, a playwright, a dramaturg, and a director.

Another important task of dramaturgs is literary management, closely following the local and global theater scene, fostering collaborations with playwrights through workshops and staged readings and discovering new talented voices. As a literary manager, you will read TONS of plays. You will develop that skill that I feel many students already practice out of necessity: to be able to tell after ten pages whether it’s worth finishing a play or not.

Lastly, as a dramaturg, you may also work closely with playwrights as they develop new works.

Aniko: Something that I see here at Skidmore is that I see so many of you, students, are such wholesome theatre artists. You fulfill so many different roles in the rehearsal room. Even if you pursue directing or acting, you may still work as a dramaturg or a designer in a lab production. This is great here at Skidmore, and it is also becoming a thing outside of Skidmore. Because it is always so helpful to have an external set of eyes, someone with a really, really good sense of theatre, a co-pilot that is the dramaturg. To have this trusting, collaborative relationship with someone is such a gift. Through stimulating discussions, you both start to understand the work so much more–there’s so much depth. It’s similar to writing: I don’t know if you have ever had this experience, but when you have to write an essay, and you feel stuck, the easiest way to pick up the phase is to try to tell a friend or a colleague what you are trying to say. Articulating your thoughts will help you to discover new directions”.

Me: “Absolutely. Something that Skidmore- theatre in general, but specifically Skidmore- has helped me with is collaboration. Something I’ve really learned here is that theatre is about working with other people, and you’re absolutely right- just talking with people. Hearing about their work, hearing about their experiences- you get to hear feedback! Being involved in theatre, you’re already going to be multifaceted- you’re already going to have so many different branches of what you do. What advice would you give students who are looking for a career in theatre, but who are mulit-faceted? You said you always wanted to do dramaturgy, but you’re also a scholar and a professor and so many different things- so what general advice do you have for students looking for a career in the theatre world?”

Aniko: “The two main pieces of advice that I have is first, get ready for a hard life, and second, only do it as long as it makes you happy. Only do it as long as you can find joy in it, and in some ways, it fulfills you. That’s the beauty of theatre; it’s a magical, spiritual, and transcendental experience. If you lose that joy, it’s okay to take a break. Sometimes life does get hard, and sometimes we do burn out. This leads to my third advice: try to be as versatile as possible. You can engage with theatre in so many ways. You can envision yourself as an artist, a practitioner, an educator, or as an activist. Stimulating yourself in so many ways will make you feel more fulfilled”.

Me: “I completely agree. If you love something, if you’re passionate about something, you should do what you’re passionate about. But you were also talking about the job you had before where you were like, ‘I wasn’t finding joy there so I went on a different path in my life’, and I think, very often, we’re told that if we’re committed, we’ll do this, this, and this, but no. Your life will inevitably go in many directions, and you will have choices to make, but ultimately you should do the thing that will bring you joy. My last question is a really simple question- how do you like Skidmore so far?”

Aniko: “It took me a little while to ease into this experience—you were in my Theater and Culture II class, so you saw this firsthand–, but now I adore the department, and I love seeing how creative and talented our students are. There is a true sense of community here. I don’t want to idolize it; I know that everyone has their fair share of struggles, I know that casting is difficult and that all the things that are difficult in a professional theater are ten times more difficult in a college environment—though not all of them… The best I can hope for is that this generous community will provide a strong foundation for all the students who graduate from this program”.

***

Max McGuire ’25 is a staff writer for the Skidmore Theater Living Newsletter