BY: GABE COHN ’16

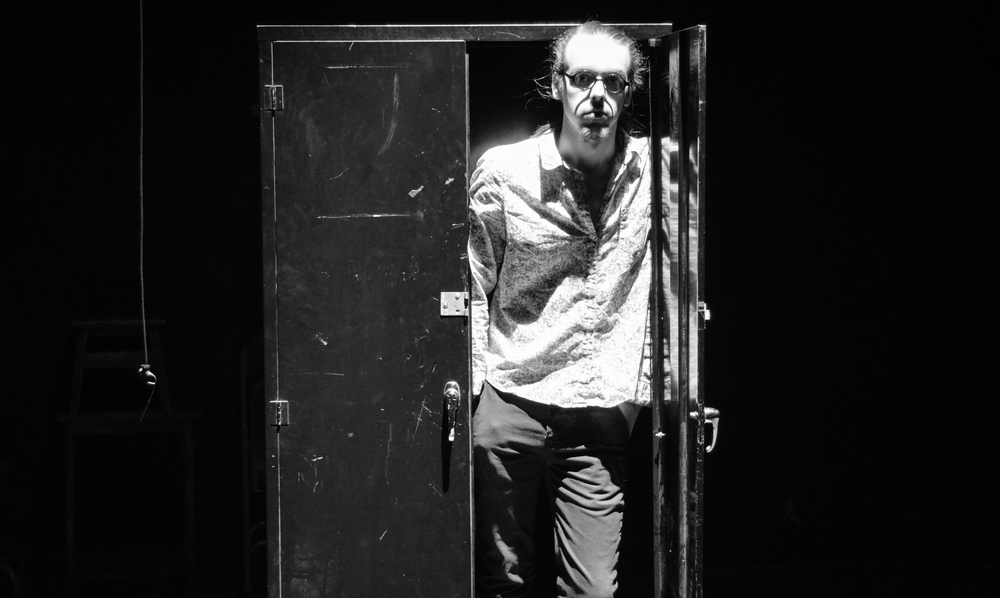

Aaron Ardisson ’16 on the set of Kaspar. Photo: Gabe Cohn ’16

KASPAR opened last night in the JKB black box. Written by 20th-century Austrian playwright/novelist Peter Handke, the play explores language and communication, often in intense and multi-sensory ways. It was directed here by Aaron Ardisson ’16. After the first performance, I met with Ardisson to discuss his experience in directing the play (his third at Skidmore, after Dacha and Trompe L’Oeil). Full disclosure: I am the sound designer for the show, and have collaborated with Ardisson in the past. After our opening night, we sat outside, lit up celebratory cigars, and had a lengthy conversation about Kaspar. The following is an edited and (very) condensed version of our conversation:

GC: Who was Kaspar Hauser?

AA: Kaspar Hauser was a German youth who emerged into society when he was sixteen. When he arrived, he could not speak. He was carrying two letters with him. The first letter was addressed to some captain—somebody of nobility. It said, “This boy’s father is dead. He would like a position in the cavalry as a cavalryman. You are free to adopt him or kill him.” It also said that he had been kept in captivity…That he’d been taught to read and write, but not speak. The second letter said that his name was Kaspar and that he was born on April 30th, 1812. That’s also my birthday, coincidentally. The fact that both letters were in the same handwriting leads some people to believe that Kaspar actually wrote both of the letters. What actually happened, nobody really knows.

What part of Kaspar Hauser are we seeing on stage?

Kaspar Hauser was a human being who emerged into society without the ability to communicate with language. He becomes a case study of how we learn language—how language allows us to function or not function within society.

In the spirit of deconstructing language, can you give me three words to describe Kaspar?

Logic.

Overload.

Abrasive.

What we see on stage in this production is Kaspar separated into many different “Kaspars,” and represented by multiple actors. Is that how it is in the script?

In the original script, it’s basically one actor on stage.

How did you arrive at what it is now?

Well, it’s a lot of text. And to be able to give enough attention to each part, I thought it was important to divide it up. Because then it’s not one actor trying to do the entire thing really well—it gives each person a smaller section to really dig into and polish. We didn’t have the time to have one person dig into the entire thing. In the original script, there are also prompters that speak to Kaspar, but they are just voices that are either pre-recorded or spoken from offstage. In this production, we brought the prompters on stage. That came from the idea of not hiding behind “theater magic,” and making it clear to the audience that they are watching a play. That was important to us.

The idea of not hiding behind “theater magic” comes through in the script, too.

Yeah. Handke writes: “The stage represents the stage…” He lays it out for us. That became a guide for us. An example: the floor of the theater still has some of the Judas paint. That’s really interesting! You don’t want to hide that.

To me, what unifies the three shows you’ve directed here (Dacha, Trompe L’Oeil, and Kaspar) is that you create your own “worlds” out of texts.

With something like Chekhov (in Dacha) or Poe (Trompe L’Oeil), there’s a large body of work and lots of characters already there. Everybody is familiar with at least some of it. So with those shows, we took all of that and tried to mash it into one room. With Kaspar, it’s not so easy. There’s not a large body of work—there’s a myth and legend of a person, and the fact that we all share the experience of learning language. That’s it.

How does that affect your approach?

I had to do less of the creating of the world and more of the filling out of the world. Handke gave us the world when he gave us the script. He was very generous in the fact that his stage directions are more “suggestions” than commands.

How does that come through in the text?

In his stage directions, Handke suggests things rather than orders them. He’ll give directions that say, “Something like this might happen.” He uses “might” a lot. There’s a tone that he uses that suggests quite a freedom of direction.

Were you attracted to that?

Yes. Mainly because I hadn’t worked with a script before. So the idea of being constrained to something like a script really scares me. Finding a script that could be manipulated was important.

Dacha and Trompe L’Oeil seemed to come from complete free-form collaboration, in the mode of devised theater, while Kaspar sees you putting your own mark on a piece of theater that already exists.

Yeah, I think that’s right. Because with the script, the playwright is also a collaborator. Handke is also a voice in the creative conversation. I can’t ignore it…Plus, it’s really good. Why would you?

How has the show changed from how you first envisioned it?

Envisioning it was difficult. Handke wrote the whole play separated into two columns—there’s a column for spoken lines and a column for stage directions on all of the pages. The actions happen while the text is being read. I saw it in my head with one person on stage going through the motions and reading the text. It was like a weird movie projected in my mind, with the one person on stage. Totally different. I feel like the movie I saw in my head was black and white and really…strange.

Well the show certainly did end up being strange.

Sure. But, like…it’s in color.

***

KASPAR runs through May 1st in the JKB black box, with performances at 8pm. For ticketing information, click HERE.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Gabe Cohn is a senior English major and Editor-in-Chief/Founder of the Living Newsletter. He has recently contributed to Culturebot, and in May will begin an editorial internship with American Theatre magazine.

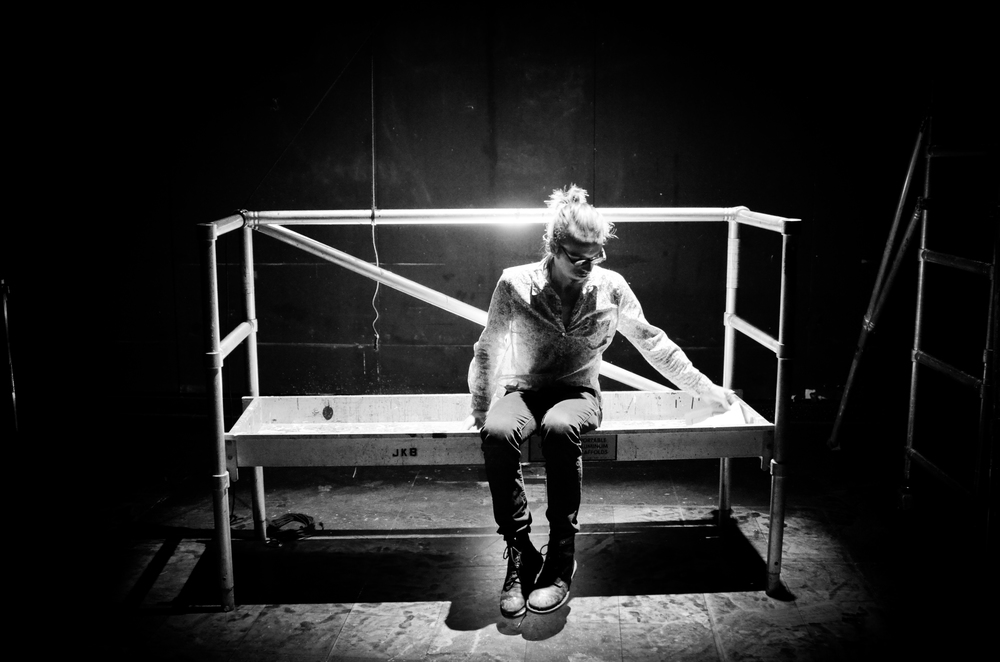

Photo: Gabe Cohn ’16