Photo: Wynn Lee ’21

By Natalie Lifson

Lights up on a living space that can only be described as “dysfunctional.” Clothes and objects are strewn about a home that looks like it hasn’t been cleaned in years. A living room is defined by the congregation of objects, complete with a beanbag chair and a makeshift kitchen created out of foldup tables and cardboard. A man lies on his back, halfway in a cardboard box. His eyes are empty. His face is painted like a clown and he wears a women’s nightgown. A woman wanders across the stage, purposefully tossing clothing with no real direction. The audience laughs. Is this funny or is this sad? We don’t know. She continues to move objects. She makes no progress.

Photo: Wynn Lee ’21

Taylor Mac’s Hir is a lot of things. It’s a family drama. It’s a play about learning to adjust when there’s something about you that’s different than it was before, and when there’s something different about someone you love at the same time. It’s about self-discovery. It’s about forgiveness and the dilemma of whether or not to grant it. It’s about the trauma of abuse and the trauma of war.

When Isaac (Anthony Nikitopoulos ’21) returns home from three years in Afghanistan after being “dishonorably discharged” for drug use, he wants nothing more than to be home, to surround himself with the familiar so he can begin to feel normal again, but he quickly discovers that everything has changed. His father Arnold (Adam Newmark ’20), once a cold, abusive man, has had a stroke and is now in the care of Isaac’s mother Paige (Emily Cross ’19), who dresses him in women’s clothing and provides him with the bare minimum needed to survive.

Photo: Wynn Lee ’21

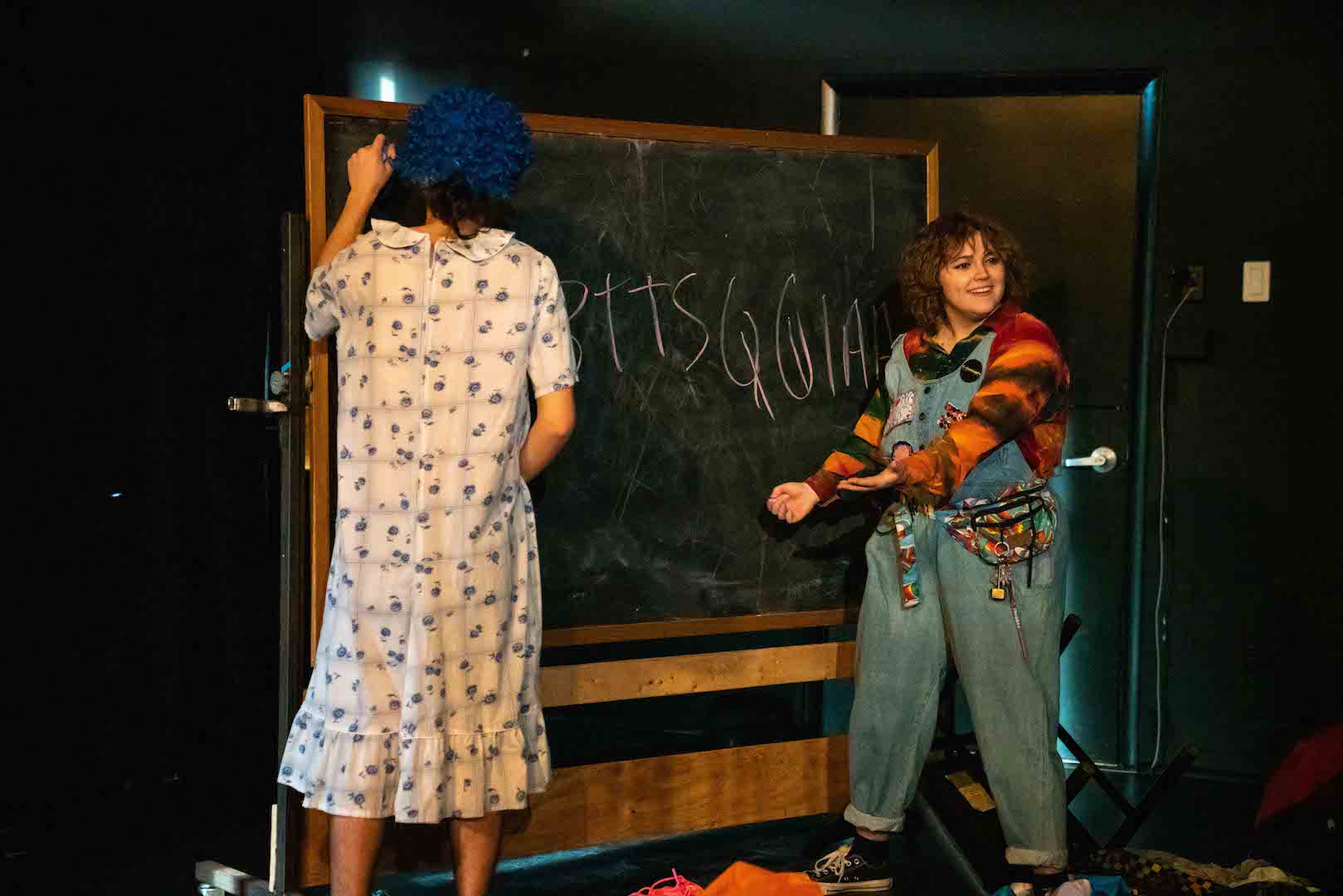

Arnold’s stroke isn’t the only surprise that greets Isaac. His little sister Max (Basil Lilien ’19) is no longer his sister, but is in the process of transitioning genders and goes by pronouns ze/hir. Isaac and Max’s relationship is strained, but familial. Nikitopoulos and Lilien portray an uncomfortable, yet loving, relationship in which both just want everything to be okay between them. Isaac and Max do not know how to understand, or even cope with, the ways in which the other has changed over the past three years.

Photo: Wynn Lee ’21

Paige is incredibly supportive of Max and is almost obnoxiously enthusiastic, but it is clear how much she loves her child. Behind Paige’s bubbly, supportive façade exists a world of pain. We might hate her for hurting the debilitated Arnold, but we can also relate to her. When Paige abandons her natural comedic state, and lets that pain and anger loose, she is a terrifying sight to behold. In her moments of anger, it is impossible to look away from Cross’s performance for even a moment. You’re afraid that if you look away, you’ll miss something.

Despite the heavy topics being discussed, Hir is startlingly funny. While the script defines the comedic moments, it is the actors who drive them to land. If Paige is terrifying in her moments of anger, in the comedic moments she is nothing short of magnetic. “Your brother’s back from the war!” she calls to Max when Isaac arrives, her tone no different than if she were calling hir down for dinner. In a play so utterly devastating, the audience lives between the jokes, waiting for something to lighten the mood before diving back in again.

Director Philip Merrick finds the space between the jokes, defines the beats, and shocks, then amuses, then horrifies, so quickly in succession that we can’t tell how we feel about the play’s events at any given moment. The tempo, which ranges from energetic to slow and defeated, lends itself to both comedy and tragedy.

Photo: Wynn Lee ’21

How do we redefine and call into question heteronormative, cisnormative nuclear family? Hir explodes the whole structure from within, ending with an outburst from Paige, in which she loses control and begins to violently spank Arnold in a burst of pent-up rage against his years of abuse. Isaac hits his mother and begins to destroy the house. His actions are eerily reminiscent of Paige’s tossing of clothes in the first scene. Paige kicks him out, and Max is left to pick up the pieces. Ze is still entrenched in the mess of the American familial past, even as ze looks toward hir own future.

PHOTO GALLERY

PRODUCTION CREDITS

Written By: Taylor Mac

Director: Philip Merrick ’19

Stage Manager and Lighting Design: Taylor Jaskula ’21

Sound Design: Basil Lilien ’19 and Anthony Nikitopoulos ’21

Dramaturg: August Sylvester ’20

Cast: Emily Cross ’19, Basil Lilien ’19, Adam Newmark ’20, Anthony Nikitopoulos ’21

***

Natalie Lifson is a Sophomore writer for STLN