When she graduated from Skidmore in 1966, Elizabeth LeCompte packed up a car and headed to Mexico. It was a year, she says, when “everybody had a guitar,” and a time when long-range planning wasn’t exactly a priority. She had some money saved up, and had met and developed a relationship with a sharply intelligent young actor named Spalding Gray. She’d been studying drawing, but didn’t trust herself to make it to graduate school. Eventually, LeCompte would stop drawing when she began designing sets (“The space became the drawing for me.”). In 1966, though, she was not so much searching for a direction as she was contentedly direction-less. Driving to Mexico with Gray seemed as good an idea as any.

LeCompte, now in her seventies, has made a name for herself as one of the most important figures in New York’s experimental theater scene. She’s director of The Wooster Group, an experimental theater company based in Manhattan that she started in the 1970’s with Gray and others, including Willem Dafoe and Kate Valk. When we spoke over the phone, she was at the Performing Garage, the Wooster Group’s home at 33 Wooster Street in SoHo.

LeCompte has earned a long list of honors, including a MacArthur Fellowship (“Genius Grant”), a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship, and the National Endowment for the Arts Distinguished Artists Fellowship for Lifetime Achievement in the American Theater. Her work with The Wooster Group has been written about extensively (most recently as the center of heated debate over performance rights for Pinter’s The Room). What is less well known, though, is the fact that her relationship with theater began in Saratoga, while she was studying fine arts at Skidmore.

Even when she was growing up, LeCompte knew that she worked best when she was collaborating: “I always liked to do things in groups, even when I was young. Back then it was being in a gang, running around town and setting fires on Halloween. But I had a good feeling for groups…I wasn’t good at working alone.” Smashing pumpkins, when done with other young hooligans, could perhaps pass as an early form of collaborative art.

After arriving at Skidmore in 1962, LeCompte quickly got herself a day job as a baker at Caffe Lena in downtown Saratoga. “I had a job there in the evenings,” says LeCompte. “Friday, Saturday, and Sunday evenings I waited tables and cooked with Lena.” She developed a working relationship with Lena Spencer, the Caffe’s eponymous owner, who around that time was beginning to develop a theater company. The Caffe had quickly gained fame for hosting a range of folk music icons including Bob Dylan and Dave Van Ronk; it had become a kind of weekend getaway for the arty outcasts of Greenwich Village, with Lena Spencer at its core.

“Lena ran away to New York in her early twenties to become an actress” says Sarah Craig, the current manager of the Caffe and a close friend of Lena. “When she had this whirlwind romance with Bill Spencer and ended up getting married, they came up [to Saratoga]…They had this idea of opening up a folk music club, but she was very motivated to have a theater as part of it. She was personally more invested in the theater.”

Times Union article, c.a. 1961. From the Caffe Lena archives, courtesy of Sarah Craig.

By the time LeCompte got to Saratoga, John Wynne-Evans, who would become a long-time figure at the Caffe, had become something of a resident director for the theater at Caffe Lena, which took on the official title of the “Gallery Theatre.” A 1961 review in the Times Union of “Telltale Heart” describes the Gallery Theatre as the sort of place where “Bill Spencer’s Siamese cat whose name seems to be Pie or Pasha—he answers to both—is likely to skitter onstage any minute and upstage everybody.” This is the cultural microcosm that LeCompte entered when she started as a baker at the Caffe.

She describes taking guitar lessons from Dave Van Ronk, the Greenwich Village folk singer whose career recently returned to the spotlight as inspiration for the Coen Brothers’ film Inside Llewyn Davis. “They actually asked me to do it. I had a little money because I worked in the summers…Some of the musicians and Lena were trying to help him, I think. And they thought that if he was teaching me, I could give him five dollars an hour. [They thought] that would give him something to do.” LeCompte laughs when she thinks about how Van Ronk would have “such a bad hangover that it’d be really hard…He was a lovely man.”

Eventually, Wynne-Evans enlisted her to help out in the Gallery Theatre. LeCompte explains: “I was on light board and I helped with costumes, and then they would drag me into doing small roles occasionally.”

LeCompte was acting, “if you want to call it that,” she says. “I couldn’t really memorize lines very well…There was this great [Skidmore] art history teacher who lived in town—James Kettlewell. He was great. And his wife, Lucy.” In the drawing room of the Kettlewell’s Victorian abode, Wynne-Evans poured sherry and tried to feed LeCompte her lines.

The most important thing to happen to LeCompte at Caffe Lena came in the form of Spalding Gray. When the two first met, Gray was a young actor from New York. “He was very involved and very committed to theater,” LeCompte remembers. Gray became a regular performer at the Caffe, acting in several of Wynne-Evan’s productions, at times opposite Lena herself. It was LeCompte and Gray, though, who would develop the strongest relationship. They quickly became involved in each other’s lives, both artistically and personally. In the rooms of Skidmore’s old campus, Gray would pose for LeCompte. “He would come to my art classes and model, and I would go and work with him on the plays.”

Spalding Gray and Lena Spencer onstage at the Gallery Theatre inside of Caffe Lena. Photograph by Joe Alper courtesy of the Joe Alper Photo Collection LLC.

The two worlds didn’t always exist harmoniously. At Skidmore, LeCompte was a Fine Arts major, with a concentration in drawing. It was about fifty years ago—LeCompte has trouble recalling names when she talks about it, and when she went to Skidmore, the college was still located at its old campus in downtown Saratoga. A figure that she remembers clearly, though, is Arnold Bittleman, a fine arts professor who taught some of her most rigorous drawing classes. “He was an incredible teacher—a real influence. I still have a portrait he gave me of himself hanging in my room.” LeCompte says that Bittleman challenged her “to do better, always. He would say, ‘You can do better than that.’ I was humiliated, but I can do better.”

Bittleman did not approve of LeCompte’s life in the theater world. “He didn’t like the fact that I was spending so much time with theater. He wanted me to go on to graduate school in art. I rebelled.” LeCompte laughs. “He was right! I didn’t listen to him. I probably should have—I would be making a lot more money.” LeCompte hints that Bittleman was a figure that she looked up to for his confidence and drive, both traits that LeCompte herself is now notorious for. “He wasn’t easy,” she says, “But he had full attention. He paid attention.”

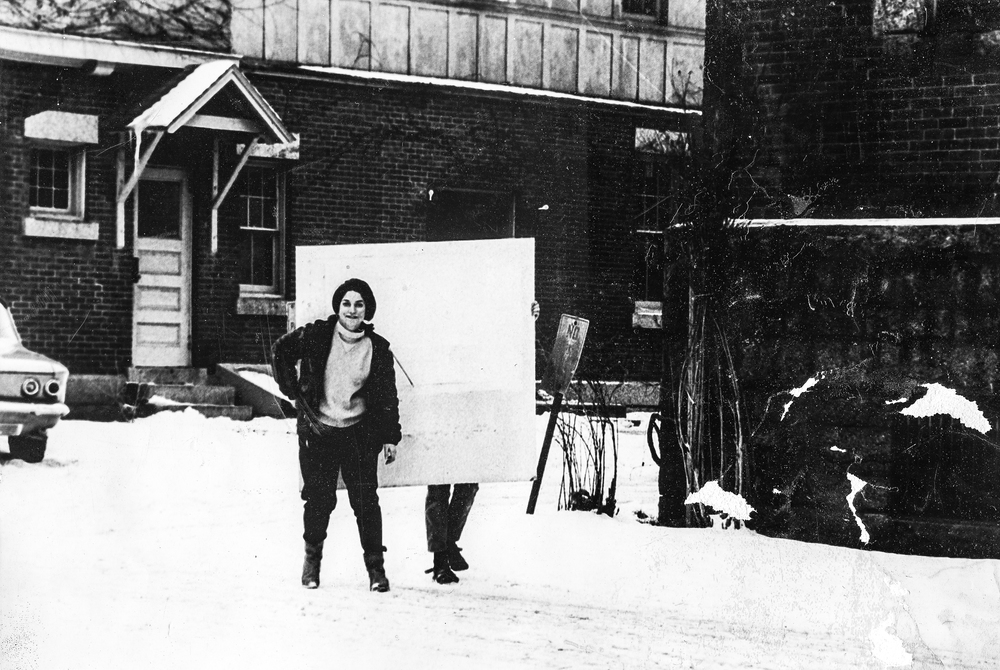

Diane Burko ’66 and Elizabeth LeCompte ’66 (obscured by homasote board). Clark Street, Saratoga circa 1965. Photo courtesy of Diane Burko.

After a brief stint in Mexico (during which Gray’s mother’s suicide would occur, prompting their return), LeCompte and Gray moved to New York. Gray started acting with the Performance Group, Richard Schechner’s experimental theater company that would eventually become The Wooster Group. LeCompte, who had set up a drawing and photography studio, would become the group’s photographer before getting involved with scenic design and, ultimately, directing.

As the Seventies rolled around, LeCompte maintained her ties to Saratoga. Her sister had opened a bookstore downtown, “The Montana Book Company,” which was around the corner from Caffe Lena. “I would go back and forth between Saratoga and New York,” she says, “I would do the book buying and bring it up in a truck.” Information on the store is somewhat scarce now (LeCompte’s sister sold it, after a few years, to a Skidmore grad, and it eventually closed), but a 1973 article in the New York Times refers to it as “a bookstore with an unusually good selection of 20th-century writing, including hard-to-find works by women and material on the Adirondacks.”

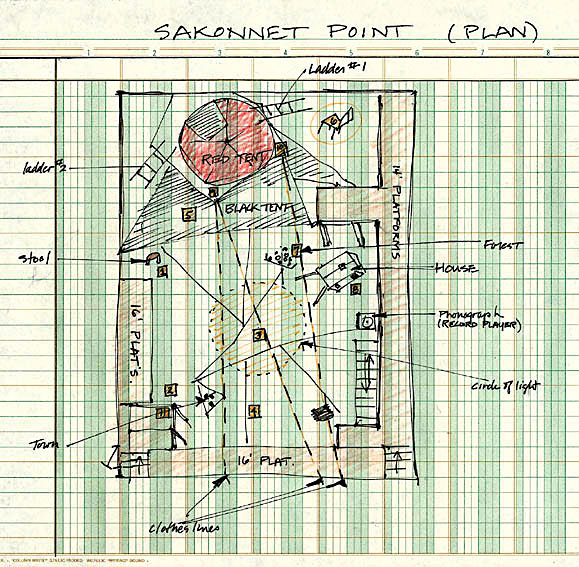

Original plan for Sakonnet Point (1975), drawn by Elizabeth LeCompte. Property of the Wooster Group.

Back in New York, LeCompte and Gray had formed their own separate group within Schechner’s Performance Group, with LeCompte as the director. Directing was a role that LeCompte “felt comfortable in right away.” She was drawn to the structure of it, and relates it to her drawing. “[It’s] very architectonic. I really enjoy the nuts and bolts of how theater equipment works—it comes from my mechanical drawing days. And I enjoy spatial anomalies and enigmatic spaces.” She was also attracted to the intense collaboration: “I wasn’t really driven. In the theater, people were there and they said ‘We have to work.’ So it gave me a structure to work.”

Willem Dafoe, Spalding Gray, Matthew Hansell, and Ron Vawter in Point Judith (an epilog), directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Photo: Nancy Campbell, c.a. 1979

Gray had become interested in deconstructing already-existing plays and creating new, intensely personal works based off of them. Here, LeCompte’s lack of traditional theater education helped shape her radical deconstructive style. “I hadn’t read the plays before I worked on them…[Gray] would take what he liked out of the play and say ‘Well, this is all I need…’ I would build pieces around those fragments. I was just trying to figure out what the play was about, always.”

Throughout her over forty years of working with The Wooster Group, LeCompte says that she has always been driven primarily by the collaborative nature of theater. Though her pieces are often birthed from very personal places (“I don’t have to make a theory or a thesis out of a play before I begin. It just comes out naturally.”), LeCompte still relishes in working closely with others. “I work with so many people, and I have to find out what their personal space is too. In that meeting of their personal place and mine, I find a new space that I never knew existed.” LeCompte is tremendously confident and headstrong, but she becomes deeply humble when referring to her collaborators. “I still count on the company to get me to work every day. If they disappeared, I think I would just go out and stare at a tree.”

Ron Vawter, Bruce Porter (rear), Spalding Gray (front), and Libby Howes in Rumstick Road (1977), directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Photo: Ken Kobland

Today, The Wooster Group still performs and rehearses primarily in the Performing Garage, though the company also performs nationally and internationally—when I spoke to LeCompte, she’d just gotten back from a short stint in Tokyo, where the group presented a recent work, Early Shaker Spirituals. Later this month, they will premiere The Town Hall Affair, a new piece exploring feminism in the 1970s. Recently, they drew attention for their take on Harold Pinter’s The Room, which had performances at REDCAT in Los Angeles. The Pinter estate, which is known for exerting tight control over all productions of Pinter’s plays, attempted to bar critics from reviewing the show. This stirred up strong reactions from the theater community, ranging from indignation (Haven’t we learned anything since Arthur Miller’s reaction to L.S.D.?) to laughter at the deep irony that, by attempting to bar critics, the Pinter estate brought a tidal wave of attention to the production in the form of numerous opinion pieces and, yes, reviews.

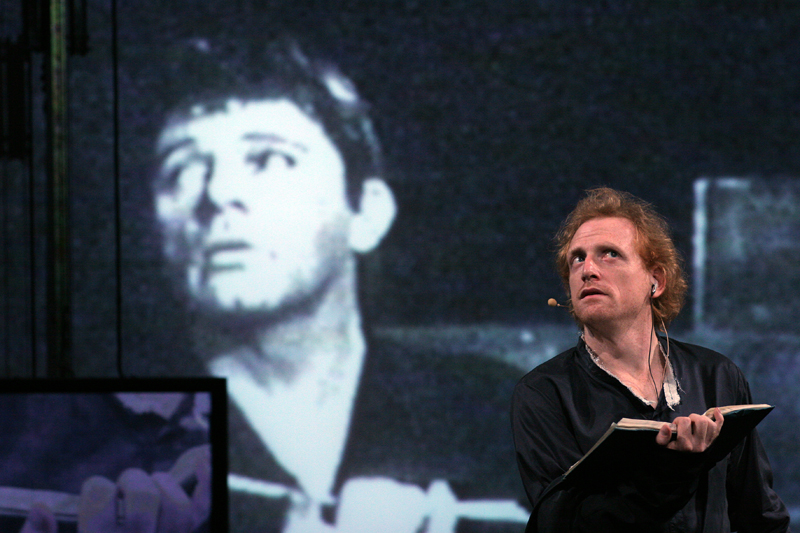

Scott Shepherd in The Wooster Group’s Hamlet (2007), directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Photo: Paula Court

As our conversation came to a close, I asked LeCompte whether she felt as though theater has a responsibility to make strong political statements, as much of The Wooster Group’s work is politically charged. “No,” she said—she was never afraid to say no. “I think whatever you’re best at, whatever gives you joy. Go there.” It was surprising to hear the words coming out of such an imposing figure. She paused, considering the thought, before adding: “And whatever gives you terror. Go there, too.” Ahh, there she is.

***

Gabe Cohn is a senior English major and Editor-in-Chief/Founder of the Living Newsletter. He has recently contributed to Culturebot, and in late May will begin an editorial internship with American Theatre magazine.

For more information on the Wooster Group, visit www.thewoostergroup.org