By Billy Winter

Kyle Thomas ’18 (left) and Sam Weinberg ’20 (right) in Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story. Photo: Dante Haughton ’19.

Kyle Thomas ’18, looking dapper in a pair of khakis and a sports jacket, sits alone on a green bench, legs crossed, reading. Fittingly, the book is The Voices Within: The History and Science of How We Talk to Ourselves by Charles Fernyhough. A bug lands on his knee briefly, but he does not notice, engrossed in his reading. This is Peter: husband and father of two girls, two cats, and two parakeets.

After a moment, Peter is interrupted by Jerry (played by Sam Weinberg ’20), who shouts that he “went to the zoo!” There is an immediately clear contrast between the two. Jerry is the foil to the calm, collected Peter. After rolling his eyes, Peter humors Jerry and gives in to the conversation.

Sam Weinberg ’20 playing Jerry. Photo: Dante Haughton ’19.

The Zoo Story by the late Edward Albee centers around a conversation between two strangers. There is almost no other action until the very end of the play. Director Lily Kamp ’18 has emphasized this focus through a minimalist set and extensive work with the two actors to heighten this connection between them.

Early on, Jerry claims that “sometimes, you have to go a very long distance out of your way to come back a short distance correctly.” Truly, this can serve as a metaphor for the play. The audience does not actually get to hear about Jerry’s trip to the zoo until the show’s climax at the end.

Jerry first lists all of his possessions, including, but not limited to: two empty picture frames, a box of collected rocks and letters, and pornographic playing cards. He touches on the divorce of his late parents and the inner workings of his sexual life (he was a “homosexual” for eleven days once). He even reveals the habits of his neighbors, one of which is reminiscent of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt’s Titus Andromedon. This is all to preface “The Story of Jerry and The Dog,” a seven-page monologue, delivered expertly by Weinberg, who manages to maintain the energy level of the room at a consistent high.

Weinberg elaborates on his process, “It is all dependent on that first moment that I walk in. And I have to build from that point and not lose the direction that I’m going [in] and just keep building and keep going and not stop to think … and not get in my head too much. I just have to keep going through the play without looking back at anything or thinking about anything else, just to be completely focused on performing this play. Just focus. Also it’s fun! It’s so much fun. I am not bored when I perform this.” Weinberg’s excitement of Thomas is evident as he fearlessly shows off his comedy chops in this tale of his attempted murder, and later, newfound love of his landlady’s monster of a dog.

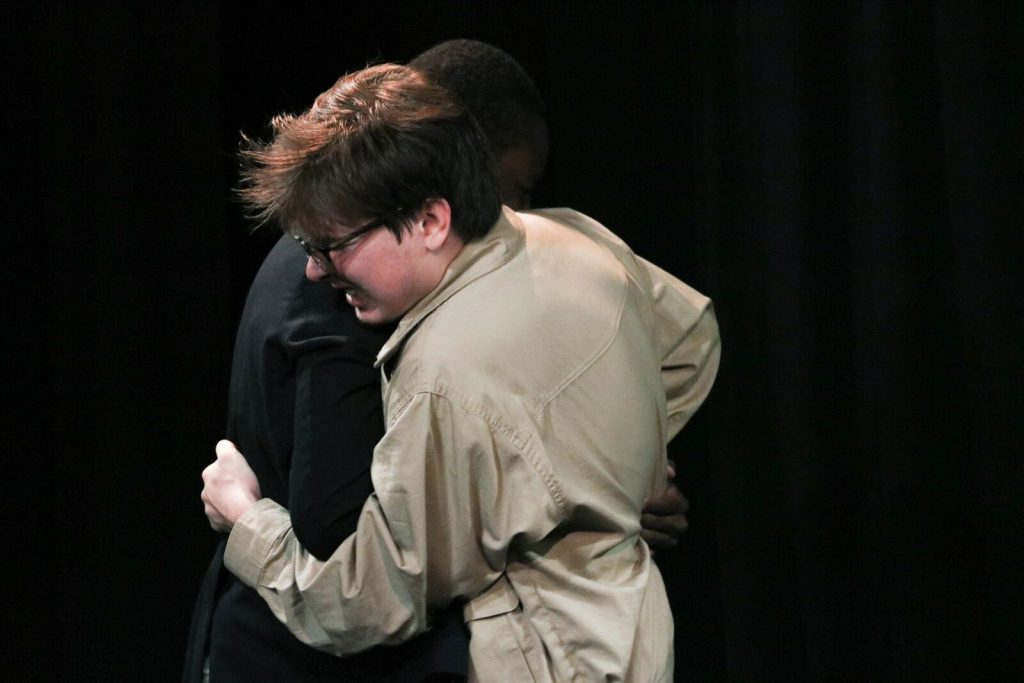

After this, the situation rapidly devolves between Jerry, who has grown increasingly neurotic, and Peter, who just wants to read his book. The two begin to argue, like toddlers, over possession of the bench, as if they were the only ones in Central Park. This quickly turns into a fistfight and, ultimately, Jerry is killed when he forces himself upon the knife he has given to Peter.

Peter (Thomas ’18) kills Jerry (Weinberg ’20). Photo: Dante Haughton ’19.

As detailed by Kamp, it becomes difficult to separate this work from the current political climate. This is pushed by Kamp’s choice of casting Kyle, an African American man, as Peter, who has suddenly become entangled in this stabbing in Central Park. I was able to speak to Lily and the cast further about how race is intrinsically tied to both this play and Kamp’s production.

“The character of Jerry’s language is written as racially charged. … And it makes anyone uncomfortable,” Kamp asserts. “We talked about if there were two Latino men up there, two white guys, two black guys, two anything, seven women. It is so weird when someone specifies race as they’re speaking because it so rarely matters or adds to your story. And so that would become an aspect regardless of who it was. And I think we’re all attentive to that. … Albee wrote it to be uncomfortable and I cast the two best actors.” When asked about what it means for Peter to be played specifically by a black man, Lily went on to say, “That’s something we talked about. And again, regardless of race, Peter—whoever plays Peter—Peter’s life is over at the end of this play … And with the knowledge we have of how African Americans have been treated by police in this country, you can infer from that what you will.”

“Lily’s completely right,” agreed Thomas. “If I was any other person, it would still feel wrong and be wrong and the same motions will be gone through. But since I’m African American, it just feels weird and it feels like it’s about me, but I really don’t think it is. It’s all about how we understand it.” Weinberg added on, “I agree with Kyle that I don’t think this play is primarily about race. It is a factor and it’s in there—definitely a part of this production—and that’s a thing you can focus on and you can get a lot of depth out of looking into that, but it’s one of the many, many, many layers between this interaction.”

Peter (Kyle Thomas ’18) listens on. Photo: Dante Haughton ’19.

Chris Monaco ’18, lighting and sound designer, who previously worked with Albee’s text on the Spring Black Box production of Fragments as well as his Intro to Directing scene, was able to expand on how Albee deals with relationship as a subject. “Albee is super interesting. I’m learning more and more about him. He loves animals and he loves looking at the relationship between humans and animals and what that says about ourselves. He loves looking at the relationships between people in a way that’s very conversational. Fragments is a conversation between seven people, The Goat is a conversation between a man and a wife, Zoo Story is a conversation between two strangers. So it’s all about communication. And it’s all about picking apart taboos of society and these different nuances of our social lives.”

The Zoo Story, like Albee’s other works, is indeed ultimately about communication. It asks how we talk with one another, as well as how we listen. What do we, as humans, need? And what happens when we don’t have someone to listen?

Photo Gallery

Production Credits

Director: Lily Kamp ’18

Lighting/Sound Design: Chris Monaco ’18

Ensemble: Sam Weinberg ’20 & Kyle Thomas ’18

***

Billy Winter ’18 is a Theater major, a Studio Arts minor with a concentration in communication design, and a staff writer for the Living Newsletter.