Learning on the Spot: An Interview with Len Jenkin

By Kallan Dana

Photo Credit: Robert Hart. http://www.theaterjones.com/ntx/features/20140113193559/2014-01-15/QA-Len-Jenkin.

Go on lenjenkin.com, and you will find a sparse, grey website. The details are minimal but clear and easy to understand. You click the “bio” tab, and you get the basic summary of the highlights of Jenkin’s arts career . Click on “contact” and a single email pops up. Click “free” and, sure enough, two downloadable PDFs of his writing are there for perusal. The site is the virtual equivalent of a straight shooter—sans frills, sans decoration, sans excess.

This online forthrightness is true to Len Jenkin’s character in person, as well. Face-to- face, he is just as direct, making furrowed-brow eye contact and answering questions succinctly. He never brags or boasts, in spite of the fact that he has much about which to brag and boast. Len Jenkin’s career is a winding road of diverse artistic pursuits, the sort of varied journey that many Skidmore students may fantasize about having after graduating. A self-described novelist, playwright, director, and screenwriter, he has found success in all of these mediums, from publication of his books, to national and international production of his plays and films, to an Emmy, three Obies, and four National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships. Oh, and he also has a PhD from Columbia in American Literature.

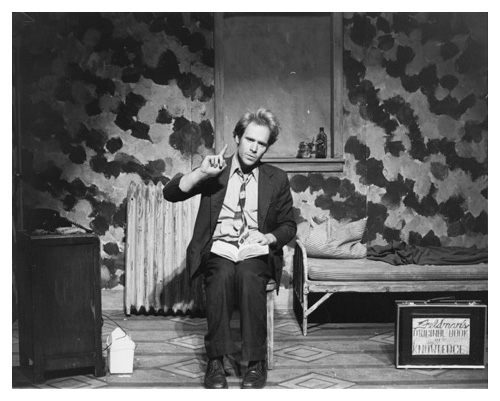

While many current students struggle to narrow down one career track, Len Jenkin is an example of how one can get away with trying everything. “I don’t have any formal training,” he states plainly. “As a playwright, I just looked at some plays and I just began to do it. I never took a playwriting course.” Jenkin’s testing-of-the-waters worked out well—the first play he ever wrote, Kitty Hawk, a Wright-brothers inspired comedy, was produced shortly after his writing it at the Lion Theatre in New York City. From that point on, he continued to write plays, teaching himself through doing. This learn-as-you-go mentality continued as Jenkin became acquainted with other art forms. As a director, he learned from watching someone else, a man named Garland Wright, the late director of the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, who directed many of Jenkin’s early plays. “I would go and watch what he did,” says Jenkin. “That was my directing class, watching Garland. It was my good luck that he was a very good director,”—a modest statement from Jenkin, a man who won an Obie award in 1981 for his direction of his own play, Limbo Tales.

Production still from Limbo Tales. http://lenjenkin.com/production_stills/production_still_lt_1.htm.

But Jenkin is sincere in his humility; almost every discipline he’s succeeded in has originated from a simple desire to just try it out and see where it takes him. While he studied American Literature in college and graduate school, he did not take on any creative-writing until after leaving Columbia, but still has gone on to publish multiple novels, though now he considers himself more of a playwright than a fiction writer. With film and television, however, “I was just looking to make a living,” he says wryly. “Some people in Los Angeles had seen work of mine for the stage, and I went out and luckily I got a few jobs writing for TV.” Ultimately, moving to L.A. led Jenkin to screenwriting credits on three films, but he doesn’t mention this in our interview, instead modestly stating that he “just sort of learned on the spot.”

He learned on the spot with playwriting, directing, screenwriting, but certainly not with reading. While he only casually mentions his doctorate in literature, his rich breadth of knowledge about literary structure deeply informs his pedagogy and sensibilities. As a writer, he has an excellent grasp of genre, and as a teacher, he encourages his students to read not only plays, but novels as well, to see films and to look at paintings. The reading list for Jenkin’s Special Topics in Plays course at Skidmore, which I was enrolled in this past semester, included the Russian classic, The Master and Margarita, and a collection of Italian folktales by Italo Calvino, both of which we used for inspiration, discussion, and, at times, devising. There was no clear end goal in mind with this syllabus, beyond seeing masterful art and finding whatever inspiration may come from it. “I never know what gets something moving,” says Jenkin. “It can be inspired by a story or image.” He is open to whatever path gets him to writing, and feels the same about his students. As a teacher, he is “open about what people accomplish,” and that rings true in how he looked student writing. He offers feedback as to what he finds appealing, but never pressures us to write the story in any one way. Rather, he wants us to follow what is compelling. For himself, he knows that his “interests are very often visual.” Interest in the visual has sparked his latest creative vocation, and the one he is most reserved about–painting.

“I painted a lot when I was younger, and, at a point, I stopped making things. About ten years ago, I took a job at the University of Madison, Wisconsin. And at one point, I went to the local Laundromat, and there was a little card there saying ’50 Dollars a Month: Join the Artist Studio,’ and I thought, ‘I think I’ll join this,’” Jenkin tells me. The Artist Studio (which may have actually had a different name; Jenkin cannot recall exactly) turned out to be a “big room where people worked on paintings,” so, on a whim, in a cold winter in Madison, Wisconsin, Jenkin began to paint again, and has kept doing it since. Self-taught, as always, he says he thinks he’s getting a little better, as he goes along.

Yet still, even as he tries other art forms, Jenkin is decisive in the medium he keeps going back to. “Theatre has people working together in a way they don’t do in film or television, or certainly [with] a novel.” Jenkin continues to learn from the theatrical field, to be roused by the new things contemporary artists are attempting everyday. “I saw a production of the Brecht play, The Good Person of Szechwan, with Taylor Mac in it, and it was a great performance, and it was directed very well. It really reinvigorated me about how much could happen onstage.” In class, Jenkin would not only have us sit around a table and read our work aloud, but would also put us up on our feet, move us around the room, layer multiple people speaking over movement, constantly seeking out something new and interesting. Sometimes we succeeded, sometimes we did not, but in all cases we learned how to be better theatre artists by doing.

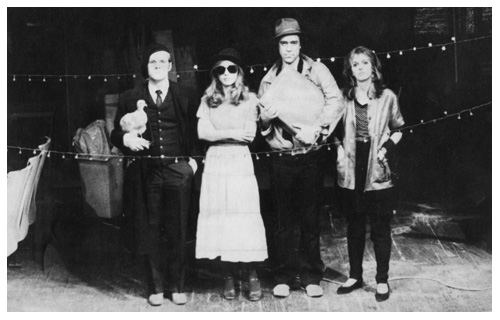

Production still from Jenkin’s Dark Ride. http://lenjenkin.com/production_stills/production_still_dr_4.htm.

Jenkin is easygoing about his relationship to his own plays. He likes writing. It’s a job, but it’s one he feels self-assured in, and one that he’s happy to be doing. Even if it is a job, and one he in many ways stumbled into doing, he feels “very lucky to be doing it.”

“I like the theatre,” Jenkin smiles, near the end of our interview. “I think it’s a kick. It’s great when the lights go on.”

***

Kallan Dana ’19 is an English/Theater double major and co Editor-in-Chief of the Living Newsletter.