By Lily Kops ’22

The Feminism Club: Nell (Stella Storino ’23), Raelynn (Isabella Kiely ’24), Ivy (Mary Mackeen ’23), and Beth (Izzy Maher ’24).

Performed in the wake of disturbing revelations on campus, John Proctor is the Villain, written by Kimberly Belflower and directed by John Michael Diresta, adds even more volume to the current conversations of sexual assault going on at Skidmore. Taking place in a small town Georgia high school circa 2019, the show follows a group of junior girls just trying to start a Feminism Club while having to confront sexual assault in the many different ways it appears in their own lives.

Through beautiful performances, the cast of students fostered a complex web of relationships and experience. Early on in the show, we witness violence and a lack of consent between recently broken up Raelynn and Lee, played by Isabella Kiely ’24 and Jonah Harrison ’22. This scene immediately calls into question the safeness of the environment we’re witnessing as an audience. For the rest of the show, that uncertainty persists and disrupts the previous small-town comforts.

Lee (Jonah Harrison ’22) talks about his relationship with Raelynn (Isabella Kiely ’24).

When Ivy, played by Mary Mackeen ’23, has to confront her dad’s sexual assault accusations, her stance on the Feminism Club is shaken, therefore affecting her friendships, in particular her relationship with self-appointed Feminism Club President and Secretary Beth, played by Izzy Maher ’22.

Further rocking the boat is the appearance of Shelby, played by Sophie Pettit ’22, who disappeared for months. Her sudden return and intense stance against Ivy’s dad puts all of the students on edge, in particular Raelynn, her ex-best friend who’s boyfriend she slept with. Finally, tensions reach their peak during one particular English class on The Crucible, in which Shelby argues with Mr. Smith, played by Will Davis Kay ‘23, and the majority that John Proctor is not the hero, but instead the villain, and reveals that before disappearing Mr. Smith and her were sexually involved. It’s at this moment that the delicate structure of the comfortable hometown is completely shattered.

Shelby (Sophie Pettit ’22) reveals her involvement with Mr. Smith (Will Davis-Kay ’23).

For the rest of the play, each character struggles to come to terms with this news and has to decide who to believe. Unsurprisingly, Shelby’s character is called into question, and rumors spread like wildfire. As the dust settles with the school board, it’s revealed that Mr. Smith will keep his job and Shelby will be removed from his class following her final project on The Crucible, in which she’s paired up with Raelynn.

Meanwhile, discomfort grows as we witness Beth and Mr. Smith together in a new light. It’s been clear throughout the show that Beth and her teacher have a close relationship, having lunch together and discussing books, to the point where Beth even calls them ‘friends.’ Maher’s portrayal of the young girl beautifully captured an internal tug-of-war between Beth’s passion for feminism and believing women, and the disbelief that a man she knows and looks up to could be like those she reads about in testimonies, unable to see past Mr. Smith’s charming façade.

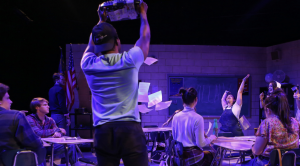

Mason (Aj Acloque ’22) holds the boom box.

When we reach the final scene, young guidance counselor Ms. Gallagher, played by Emily Zeller ’22, converses with Mr. Smith before Shelby’s final presentation about her role as a mediator. Mr. Smith pitifully asks her if she believes him, and she then reveals name after name, woman after woman who in the past have spoken out against him, and speculates how curious it is that all those girls just happen to be ‘crazy.’ When the students enter, the tension remains, and the recently reunited Raelynn and Shelby perform a scene between Abigail and Elizabeth Proctor, indirectly confronting their own assaulters and then bursting into a dance, reminiscent of those accused witches dancing in the woods.

They dance and dance, soon to be joined by Nell, played by Stella Storino ’23, who blocks Mr. Smith in his attempt to stop them. When Mason, played by AJ Acloque ’22, stands in his own support, he grabs the boombox from Nell and holds it high above his head, staring directly at Mr. Smith. Acloque’s simple gesture of defiance was a stunning and powerful moment and a beautiful culmination of Mason’s journey throughout the play.

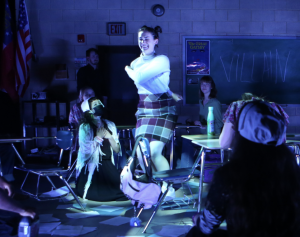

Beth (Izzy Maher ’22) dances.

In the defining moment of the play, one that sent shivers down my spine and brought tears to my eyes, the dancing students stopped, knelt down, and turned to Beth, still seated in her chair. The lights went blue and focused, and the sound of waves rushed in to join the music. At this moment, Maher had to make a decision each night: to stand and dance, or to stay seated. This aspect of the play brought so much weight, reminding us that this is her future, that every young girl, every young survivor goes on to something else, and for Beth, as an image of Kimberly Bellflower herself, she has an after. The night I saw it, after a moment of hesitation, Beth stood, and she danced. She danced and cried and smiled, and that dance told a million stories. When the lights went out I couldn’t help but feel extremely empowered and deeply satisfied.

***

Lily Kops ’22 is a Staff Writer for the Skidmore Theater Living Newsletter